BONES OF THE CHINAMEN

A novella by Dean Barrett

DOUBLE ISLAND, SWATOW, CHINA, LATE 1800'S

I have much to apologize for. That much is clear. But before I divulge my transgressions after which you will without question be repulsed by the horrific nature of my crimes - I must apologize for the odor. What little ventilation we have is through the crevices of the venetians and through the front entrance when the thick pitch pine door is open. Which it seldom is. The door at the rear is always locked except when the outside kitchen staff carries in the baskets of coarse rice and poor quality tea in narrow-mouthed earthen pots. And when the tall jars overflowing with urine and excrement are removed from the terrace through the same door. The only other door is upstairs; a less sturdy door which opens onto the terrace and the terrace is all the coolies have for a privy. The terrace is, of course, too high for a coolie to jump down and escape...although some try.

But I think it best before I begin if you know something about me. I am Li Tong, a Canton man of the clan Loi. I was born in Goose Run Village during the year of the dragon, hour of the tiger. As my father was a merchant, I could never hope to sit for the imperial examinations and so I joined my father in his printing and binding shop. And there I read all of the classics of Chinese literature. I soon realized I had a passion for learning and I loved to sit under the shade trees and listen to the itinerant story tellers who traveled from village to village filling our eager minds with outrageous gossip and tales of adventures and news of outside-the-province people.

And then one day another story teller came. He was a foreign-devil with green eyes and a long nose. He was dressed all in black with a high hat and a large cross and he carried what he said was a holy book. I listened to his tales about the son of his god who had come to save us but who was mocked and murdered. And of how the son would come again. And of how we should be ready. And he built a place for those of us who wished to worship his god, and even the Manchu soldiers did not interfere with him so we knew he must have great power.

My father did not approve of the man or believe in his three-in-one god but he did not know I spent much time with the foreign-devil story teller. I listened to his exotic tales of wars and bravery and betrayal and death and then one day I told him I believed what he said. And I did the great washee and then I too wore a cross. And my father said I was a fool and he beat me. The foreign-devil story teller traveled on to another province, but then the chang-mow came. We called them chang-mow or “long hair,” because they did not shave their heads or wear a queue but left their hair long in the previous Ming Dynasty style.”

They slaughtered many of us and would have killed me but they too worship the three-fold god of the foreign-devils. So when they saw my cross, my family and I were allowed to live. After that we moved to Swatow where my father’s business grew rapidly and where I learned the ways of a Christian. And I met a woman I loved very much. And for a few years, I was very happy. But that is all gone now. Now I work here. This is a barracoon. A building which serves as a holding pen for slaves. A hellish world in which slaves are gathered and inspected before they are shipped out.

The barracoon is in southern China at Swatow, on a sandy island at the mouth of the river; an island known to the foreign devils as Double Island. Imported goods – smuggled or otherwise – are shipped upriver to the city of Chaochowfu. And Chinese coolies are shipped across the great seas to foreign lands, wherever the foreign-devils can sell them at the highest price.

The barracoon has been here for several decades; as have I.And this - this is a two-stringed Chinese fiddle: an er-hu. The foreign-devils say the melodies I play are almost painfully beautiful, melancholy, plaintive and heartbreaking. My father always said it was the perfect instrument to express emotions. I have learned that it is certainly the perfect instrument to express pain.

In any case, I play music here; I will play music here until I die. That day will not be far off; but before I journey to the Land of the Yellow Springs I want you to know the truth about what happened in this barracoon when I was still young. When I worked here as a free man. For the rumors about me are as fanciful as they are numerous and I urge you not to believe them. They are told by people who were not here. People who were not even in China at that time. People who have no right to judge.

Whatever you might have heard, I neither sold coolie slaves nor was I a coolie who had been enslaved. I simply served the various foreign-devils who ran the barracoons and sailed the coolie ships. I had learned English well from missionaries and in my father's shop I had worked with numbers and receipts and an abacus. These skills made me valuable to the foreign-devils who derived their profit from the coolie trade.

It was a time when China was in turmoil and many had little or no food. In that turmoil, my father lost everything, and I was content to make money as I could; but I wish to emphasize that I was not one of those known as a “crimp,” a Chinese who kidnapped his own people and sold them to foreigners. As I said, I simply served the foreign-devils. And so I could live. And I could live with myself. Then, one day, on the 15th day of the seventh month, during the time of the year we call Cold Dew, everything changed. And yet, except for the storm, known today as The Great Storm, it was a day which began much as any other.

I had overslept but it was still early morning when I made my way on foot from my one-room lodging at a cheap Swatow inn, fighting the howling wind and heavy rain every step of the way. I had secured my flat-brimmed tarpaulin hat by wrapping my queue around it but the wind squalls threatened to undo the fastening at any moment.

The barracoon was surrounded by flat open land, a sandy soil wasteland barren of all but a few scraggly mulberry trees and unattended fields now overgrown with weeds. I could see several wild geese completely trapped, desperately flapping their soiled and waterlogged wings in an attempt to achieve freedom. With each step I took, it became a more difficult task to avoid becoming mired in a sea of dark brown muck. At one point, I was nearly blown into a concrete vat’s collection of nightsoil, human manure for crops.

I had never before failed to make out the massive granite boulders on the barren hills surrounding the port but the wind-driven rain blurred my vision and turned the parched earth to slime.

The winding path I was on circled and zigzagged back and forth, a design meant to disorient any avenging spirits from following those who left bodies here. But in my confusion, not far from the barracoon, I strayed from the narrow footpath and my feet slipped from under me. I fell forward, hard to the ground. A few drops of red appeared on my wrist but were quickly washed away by the relentless rain. There was a sudden flash of lightning in the northern sky and I saw that I had cut myself on shards of pottery which I now realized lay embedded in the mud in every direction.The injury was minor but I knew glass and pottery were mixed with lime over the graves of the poor so that pigs and dogs might not dig up the bodies. The driving rain pounded the earth and as I lay sprawled on my belly, I saw – or imagined I saw - something white just beneath the soil. The wind and rain were working frantically together to unearth what was below yet it appeared as if whatever was buried was itself struggling to dislodge the soil; and at the thought of the bones of the dead I struggled desperately to push myself up and rush from a spot where there might be avenging ghosts.

Minutes later, heart pounding wildly in my chest, I finally glimpsed the barracoon. Barely visible in the storm, the building seemed to soar beyond its mere two stories and it stood out against the morning mist as an imposing, black silhouette which bid no one welcome. The tempest battered its wooden China fir frame with force and fury as if its sole purpose were to destroy it. Sheets of rain swept from one end of the tiled roof to the other, and it appeared that the barracoon itself was a living thing, as if the thunderous moans emanated not from the wind but from the barracoon, an enraged beast maddened by the fury of the storm but unable to escape.

I struggled along a path beside the kitchen, its narrow chimney inactive and forlorn, some minor outbuildings for tools, kitchen utensils and weapons, tinned goods and oil lamps, and sacks in which to bury or to abandon the dead: coolies who had died of disease, from punishment or by their own hand.

I arrived soaking wet and still flustered from my ordeal and pounded on the door until the somnolent guards finally let me in. Even these burly men had some difficulty in shutting the door against the fury of the wind and torrential rain.

The first thing I remember when I stepped inside that day was the sound of hammering: three coolies had attempted escape the night before and the wooden venetians at the windows were being nailed shut to prevent any future attempts. I especially remember how, as the light gradually dimmed, it crossed the floor in streaks, like the bars of a prison. And so inside much of the barracoon daytime was to become hardly distinguishable from night.

Until last year, the barracoon had been lit by tallow candles coated with wax and with oil lamps, but recently someone brought in a set of silver-plated Argand lamps and replaced the blubber-oil of the right whale with costly sperm oil, and so, much of the excess smoke and noxious odors from inferior lamps and poor quality Chinese candles which once permeated the barracoon are gone. In any case, after the hammering finally stopped, there was even less outside light seeping through the venetians.

In addition to this one large room there were narrow stairs leading to a cockloft above, a bamboo-floored platform about six feet above our heads, where there were still more coolies. The coolies milled about only within the northeast side of the building, both upstairs and down. They were not shackled in any way but they knew precisely what area of the barracoon was theirs to move about in. Their space had no lamps or beds but only a scattering of foul-smelling straw and vermin-infested gunny bags to serve as sleeping mats.

I remember the often distorted shadows of these men shuffling about in the background while waiting to be examined; emaciated apparitions silently flitting between lanterns and smoking candles until once again absorbed by the darkness. The stairs are still here but there are now so few coolies that a room has been built on the north side of the cockloft in which foreign-devil ship captains sometimes sleep.

When I first came to work here as a young man it was during the height of the slave trade, and there were usually about three hundred men in the barracoon. All Chinese coolies. Not counting their jailers, of course. The jailers were as they are now: Portuguese, Brazilian and mixed-blood Chinese-Portuguese from Macau. And some, I am ashamed to say, were pure Chinese. The coolies thought they were waiting for a ship to take them to Macau to work or to Gum San – “the Gold Country...California;" but they were not. And that is why the downstairs doors were locked and barred and the venetians were nailed shut and the keepers had keys and guns and knives and swords and rattan rods and leather whips.

As repulsive as they are now, the odors were worse then. I have to smile when I remember that, despite all that he was, Armindo was the only one who cared about the smell. So every day just before he arrived, one of the guards lit joss-sticks - sticks of incense; and soon the sandalwood aroma hid the offensive odors...just as the music played by the coolie musicians was used to hide the screams of coolies being whipped. Armindo was- forgive me; I have forgotten how much time has passed. In here it is so easy to forget. Armindo DaCruz. You would most probably not know that name. Consider yourself fortunate. Because, believe me, had you lived in southern China when I was a young man, you would have known it then. And had you displeased him in any way, it would have been the last sound in your consciousness before you slept and the first sound in your consciousness before you woke. Armindo DaCruz.

Armindo was the only man I knew about which I could say that whatever he was, he was to perfection. Yes, he was tall and well built but he did not dominate by his unusual stature and his unbending will alone. Inside Armindo was a destructive, even self-destructive, intensity as passionate as it was irresistible.

Some of the foreign-devil slave sellers who came to the barracoon were the cruelest, most dangerous men on earth. Men from many nations who had survived only by making certain that those opposing them did not. And yet I never failed to see Armindo intimidate such men and impose his will on them. Indeed, none dared even raise his voice to Armindo. It was not simply that they knew he feared nothing; it was as if they sensed that whatever it was that inhabited his tortured soul was not quite human.

He was in his late 30’s or early 40’s

. An ex-seaman and an expert at surviving in a very dangerous world. He was swarthy with leathery skin and raven-black hair. His features were craggy and angular. He had thick black eyebrows beneath a high forehead. His eyes were charcoal gray, the same cold shade of grey as the ash left by the joss-sticks my father burned in his village temple. He had a prominent nose and full lips. His large hands were square but his fingers were tapered and surprisingly elegant.I learned very few facts about Armindo’s background from Armindo himself. But from Dr. Murray I knew he was the second of two sons from an impoverished family which had eked out a living in the desolate mountain area of northeastern Portugal; an area called tray-os-montes, “Back of the Mountains”. It was a region of remote villages and deeply devout Catholicism. While still a young man he and his brother had survived a disastrous drought and left for the central coastal region where they worked fishing fleets before he’d had to flee Portugal for killing a man. Dr. Murray knew little about the murder except that it involved a very beautiful but ultimately unfaithful woman. Armindo had then spent most of his time along the China Coast, and at various times, had been involved in smuggling arms or smuggling men in such places as Manila, Macau and Hong Kong.

If I had to sum him up in one phrase, it would be an intensity of purpose. His anger, his laughter, his indignation, whatever it was was somehow more absolute, more focused - I almost want to say more pure - than that of other men. As if some demon inside him drove him on. There was in such a nature no room for insincerity or pretense and absolutely no room for weakness. When I look back I have to say I can never remember even a moment when Armindo feared anything.

It was at Armindo’s urging that I had changed my outside rainwear from the coconut fibre typical in the Swatow region to the attire of Westerners. I still wore my green quilted tunic and baggy breeches underneath but when the rains were torrential as they were that day, I dressed so that, as Armindo said, at a distance none could distinguish me from one of them.

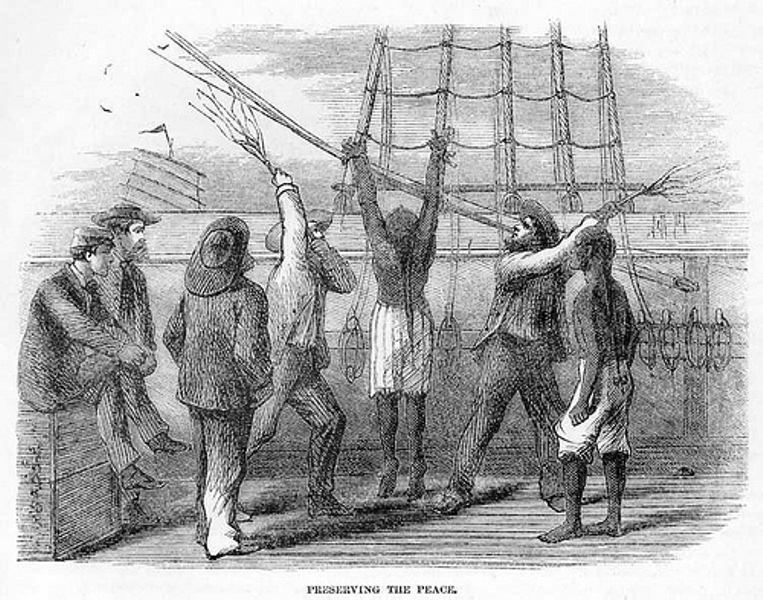

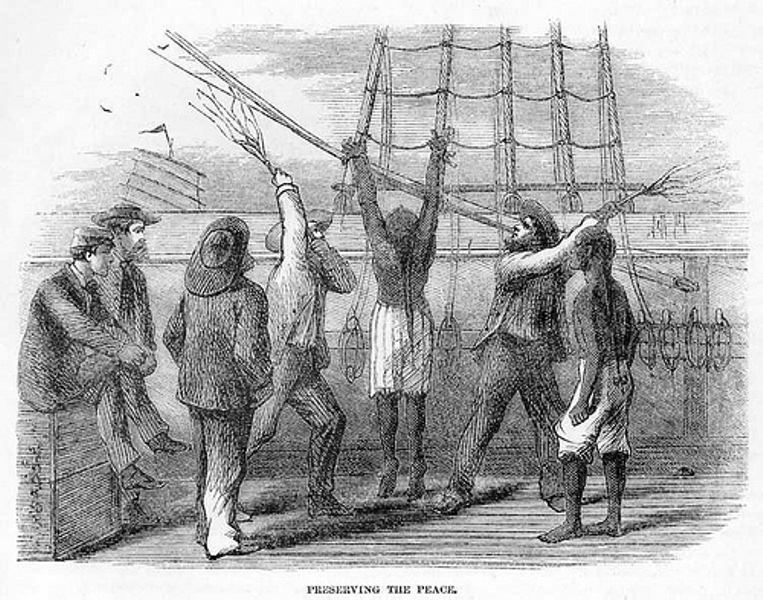

And so as I entered the barracoon that day, with hands shivering from cold, I untied my queue and unwound it from around my tarpaulin hat and stripped off my pea-coat, the thick, coarse double-breasted jacket Armindo had given me. I turned to place them on a wall peg. By then my eyes had adjusted to the semi-darkness and what I saw before me drained the blood from my face. Within a few yards of where I stood were two bound coolies.

The closest was emaciated and completely naked. His long matted hair and thumbs and large toes had been bound up together and he was hanging like a sack of rice from a ceiling beam, his back and buttocks just inches from the floor's packed earth. His head fell backward, and from where I stood I looked down directly into his face. His body was bruised, his lips swollen, and his eyes shut. He swayed ever so slightly like a sailor’s rope bed on board an anchored ship. His breathing had a strange and unnerving gurgling sound which rose almost to a groan but then died out until he breathed in again.

The second coolie was young and well built. He wore nothing but a filthy loincloth and had been tied to hang facing the far wall. His back was crisscrossed with purplish black welts upon which was dried blood and crusted gore. His hands had been bound in front of him and they were swollen from having been tightly shackled. He was tied in place by his queue to the wooden wall peg I had been prepared to place my coat and hat upon. His plaited queue had been shortened in length by being wrapped about the peg so that he could not sit down or attempt any movement without painfully pulling his hair.

The Manchus had ruled us since the mid-17th century and had imposed their style of hair upon us by force until, human nature being what it is, we began to take great pride in our queues and genuine horror and humiliation should they be severed. So, as was the case with all Chinese males including myself, part of his crown had been shaved and the remaining hair at the back of his head had been braided into a long queue. Many of the men working in the barracoon let their plaited queues hang behind their backs, but most of those who had the misfortune of passing through the barracoon were coolies and they kept their queues tightly plaited and up in a bun at the nape of their neck or else coiled around their head.

Men with pistols or knives stuck into their belts - both Chinese and mixed blood Portuguese-Chinese - were observing a furious hatchet-faced Spaniard whip the coolie whose queue fixed him in place. I could detect no movement from him of any kind and had he not screamed would have assumed he had passed out from the pain of being whipped.

I had not been working in the barracoon for long, and in the low light, I at first thought the long, black objects hanging from the Portuguese's belt were clubs but then I recognized them as the severed queues of Chinese men.

The screams of the coolie rose and died out and, in the brief silences before he was lashed again, I heard the familiar grunts and curses of the Chinese crimps and guards in the darkness at the back of the room. They always bet heavily on their dice games and when luck was against them their own groans of "Aiiyaahh!" mingled with the screams of the coolies. They took no interest in the beatings as the beatings were nothing new to them.

A few yards away, in the area set aside for them, frightened musicians played their music - with the docile air of men desperately afraid of being beaten. The elderly, wizened opium addict from Canton stood over his drum, beating it for all he was worth, sweat pouring from his forehead. The dark-complexioned Tujia Chinese from the mountains of western Hunan frantically beat his gong with his stick, and the hollow-eyed er-hu player, agitated as a mad man, joined in on the tune. And so, at each enormous crack of a whip on flesh the sound of a blood-curdling scream was lost in the loud and discordant and cacophonous music.

I stood immobile, holding the tarpaulin hat and monkey jacket, not quite certain where I should hang them. As my eyes slowly became accustomed to the dark, I could glimpse other coolies peering out at the scene from the darkness.

It was nearly time for Armindo to appear and like clockwork two Chinese crimps began swishing lighted sandalwood incense sticks about as they crossed and re-crossed the barracoon. Lingering, unpleasant odors had more than once triggered Armindo’s quick temper and they were determined never again to be the objects of his wrath.

I hung my wet clothes on a peg sufficiently out of reach of any whips or bamboo rods then joined with Chinese guards lighting candles and turning up the oil lamps. I entered the tiny kitchen area within the barracoon itself to prepare tea and congee. Armindo liked both his tea and congee flavored with ginger, especially on wet and cold mornings such as this.

Although I did no cooking for the coolie slaves or crimps, I would sometimes prepare fruit or toast or congee or even dumplings for Armindo, Dr. Murray and Captain Elliott. There was only a tiny skylight above the cooking area, which was often blocked, blackening the walls with the accumulation of years of soot.

I picked up the iron kettle, filled it from the water jar, and placed some wood underneath the clay stove. After I lit it, I took a small saucer from a shelf and a preserving jar from a cupboard. I placed upon the saucer winter lichees from Canton and a huge pile of dried pips of melons. I had to constantly feed the fire as the wood never seemed dry enough, no matter in what way we covered it.

I removed the bamboo matting from a porcelain vase and used a scoop to remove long, thin tea leaves. I knew

the firm and compact Hyson leaves would take more time to unfold than the leaves of black tea and I stared at them willing them to infuse the water quickly so I could have a bit of tea before beginning work.I placed lumps of heated charcoal inside a small brass brazier and inside a smaller copper one. The larger of the two I placed at my feet and I used the smaller one to warm my hands.

I managed to gulp down a half a cup of tea and a bowl of rice with vegetables, but the congee was still cooling in the earthenware basin when

I heard loud pounding on the door. I remember the sound as if it happened only moments ago. I always knew when it was Armindo who pounded. It seemed as if it was something more than a human behind the door, and the sounds of his fist against the pine could be heard above the music and above the whipping. And above the screams.I rushed from the kitchen to the door and aided a guard in sliding the wooden bar through the latch. Flattening one cheek and my body against it, I strained to keep the open door from smashing inward. I could hear the howling wind and driving rain and knew the storm was increasing in intensity. The pinewood door always had a peculiar but pleasant smell when it was wet, triggering memories of long walks outside Canton with my father when I was a boy.

Armindo’s flat-brimmed tarpaulin hat, black monkey jacket and black leather boots were wet and shining from the rain. Drops of water fell from his thick black eyebrows onto the long lashes above his grey eyes and coursed down his cheeks. I held out a towel and greeted him but just as he was about to respond he heard the sound of the whip and he quickly brushed past me. The coolie being whipped had grown silent but the musicians continued to play.

Armindo observed the whipping for just a few moments before moving quickly to observe the coolie close up, then stepped up to the Spaniard, spun him about and grasped his wrist. “What the devil you whipping him for?”

The man’s eyes narrowed. “What!”

Armindo turned to the musicians. “Stop that infernal noise, you heathen devils!”

The musicians quickly disappeared into the darkness, their long queues trailing behind them.

“I said, what the devil you whipping him for?”

The man made a brief but strenuous effort to pull his arm away from Armindo’s grasp but, realizing it was hopeless, gave it up. “Bloody heathen's still refusin' to sign his contract!”

Armindo released the Spaniard’s arm and grasped the man's face with both hands. By this method, he maneuvered the Spaniard behind the coolie and pushed the man’s face to within an inch of the coolie’s face. “The Chinaman is dead, you damn fool!”

Armindo released the man and the man stepped back. He stared at the coolie, then lowered his whip. His malicious grin revealed a silver tooth. “What's one coolie more or less?”

Armindo drew his sheath knife so quickly it was just a blur of motion. He used his other hand to shove the man violently into the wall, nearly toppling an oil lamp. For several seconds, the agitated flame brought Armindo and the Spaniard in and out of shadow. “That's thirty Spanish dollars I lost! I ought to cut your heart out! If you don't know how to whip coolies without killin' 'em, get the hell out!” Armindo tossed his knife from hand to hand with obvious skill and stared at the man seemingly without emotion but tensed to kill. “Unless you'd like to try me.”

With each toss of the knife, the razor-sharp blade was caught in the glow of the oil lamp and my eyes followed its silvery arc as a man trapped in a vivid but terrifying dream. I had always hated violence but there was something almost beautiful in Armindo’s displays of fury. For I had no doubt what fire lay beneath the cold surface of his ash grey eyes.

The Spaniard hesitated, then started to move quickly away. He had not walked more than a few feet when Armindo’s blade whizzed past his ear and stuck fast and loud into a pillar beside him. The frightened slave trader turned back to Armindo. Armindo gestured toward the queues at the man’s belt. “I’ll be having those.”

The man hesitated only a second then walked to Armindo, removing the queues as he walked. Armindo took them and tucked them into his own belt. As the man turned and walked again, Armindo said, “And I’ll have my blade back.”

This time there was no hesitation. The Spaniard exerted a series of tugs and pulled out the knife, then walked to Armindo. I held my breath. The Spaniard held it out to him, hilt first. Armindo had left himself completely open to a quick thrust of the knife had it been the man’s intention and I could feel my heart pounding wildly.

After several seconds, Armindo smiled at him coldly and grasped his knife. “Don’t ever kill one of my Chinamen again.” The man nodded and walked off.

Armindo gestured to the Chinese guards to cut the coolie down. Without being told they knew to take him from the barracoon, place him in a coarse sack and to leave him in the sand near the river. It was then I remembered the bones; and the seemingly unnatural manner in which they were being uncovered.

Armindo replaced his knife, stripped off his jacket and hat, and looked about. “Li Tong...Li Tong!”

I snapped out of my reverie and rushed to take his hat and jacket. I hung them up carefully on wall pegs.

“I'm chilled to the bone. Hurry up with the tea.”

“Yes, sir. I'm sorry. I overslept.”

“And it’s bloody cold out there. You can add a bit of ginger to it.”

“I have done that, sir. It is all prepared.”

When I returned with his tea and fruit, and a brazier for his feet, Armindo had sat at the long wooden table and was removing his two pearl-handled pistols from his belt. As he drank his tea, he carefully examined the powder in the pistols' priming pans, then changed the flint in each cock. With infinite care he cleared the barrels with his ramrod. I knew he carried a revolver inside his clothes, tucked inside a leather pouch close to his chest, but he fancied his pearl-handled flintlocks; given to him, so he said, by his father.

He wore a black-and-emerald green flannel shirt, black leather vest and striped merino trousers. He wore no pocket watch but his knife was sheathed at his belt and a small cross hung about his neck from a silver chain.

Armindo was especially agile with chopsticks and he had his own made of ivory tipped with silver. He reached over, trapped the white, fleshy pulp of a lichee and popped it into his mouth. His features relaxed just a bit as he savored the fruit then returned to their usual alertness. “And how many times have I told you: when we got a storm, we don't need the damn heathen music! Nobody out there can hear anybody screamin' in here during a typhoon! Tell the buffle-headed musicians not to play except when they're needed or I'll ship them out!”

“I am sorry, sir. It won't happen again.”

At the sound of pounding Chinese guards again opened the door. Dr. Murry, our British physician, staggered in, practically blown in by the storm, and immediately collided with the Chinese carrying the coolie’s body out. He managed to clutch his leather bag but his walking cane was knocked from his grasp. He uttered an oath but stepped aside to let the guards pass with their burden. A guard picked up the cane by its ivory handle and held it out for him. As he stripped off his peacoat I took it from him and hung it on a wall peg.

Dr. Murray was a rotund man in his mid-fifties, with a round, oily face framed by curly white hair and long sideburns, and, regardless of his choice of apparel, never failed to appear rather shabbily dressed. His black frock coat was well worn and I seldom saw him in anything but old serge trousers and inexpensive gray or black flannel shirts. He seemed to take pride only in his gold watch chain from which a small silver anchor hung as a charm and in his ivory-handled, initialed, walking cane.

His silver-rimmed spectacles were always propped halfway down his protuberant nose. His large pores, prominent veins and red complexion revealed unmistakable signs of a life of dissipation. Except for those occasions on which he had had too much to drink - at which time he often spoke very quickly and, according to Armindo, in his original lower class accent - I had no problems understanding him.

He attempted to retain his dignity but appeared unsteady on his feet and had difficulty repressing a bad cough. He wiped his spectacles with his handkerchief. “Mornin', Li Tong. Glad to see you here. The other so-called interpreters know about as much English as I know Chinese.”

“Thank you, Dr. Murray. I arrived late because of the storm. But I’ll get you a brazier. You'd better dry off.”

I handed him a towel. He rubbed his face and arms.

“I wager this weather'll be the death of me yet. And the lightning’s in the north sky, so we can expect a lot more of this misery before it’s over.” He motioned toward the door. “What was that about? Not dead of disease, I hope? If so, I need to examine him.”

“No, sir. He died of a beating.”

“Well, that’s a relief: No contagion for us to worry about and no more hell on earth for that poor creature.”

He handed me back the towel and carefully removed his bowler hat from the leather sack he carried into the barracoon each day. He examined the hat for damage while speaking. “The rains loosened the sand. Bones of Chinamen are exposed all along the north shore of the island. The lucky ones had coffins. But now the sand has shifted and their coffins are bein' swept out into the river. Most peculiar sight I’ve ever seen. Poor bastards had no peace in life and now-“

Armindo spoke without looking up from his weapons. “You're late, Dr. Murray.”

“I was detained.”

“By a bawdy house bottle and a more-than-willing chick-a-biddy, I'll wager.”

“Chick-a-biddy?” He handed me the towel and with utmost care placed his hat on his head. “At my age I consider myself fortunate if I manage to enjoy a few moments pleasure with a wrinkle-bellied hedge whore. But, no, my dear Armindo, I was in point of fact detained by the emigration agent.”

“What the bloody 'ell does he want?”

“He boarded the clipper and ordered your crew to reland the pork.”

“Reland the- What the hell is wrong with the pork?”

Armindo jammed the pistols in his belt and stood up.

“Maggots. Small maggots, to be sure, but it seems he has discovered them in the deepest recesses of the joints and he wishes me to remind you that according to the Chinese Passenger Act-“

Armindo snatched an iron-handled whip from the wall. “I don't want to hear about the bloody Chinese Passenger Act! Of course the bloody pork has maggots: The chuckle-headed Chinamen dry salt it instead of keeping it in brine.”

Dr. Murray placed his leather doctor's bag on a table and sat in a chair behind it. I approached him with a cup of tea but as I expected he waved it away. “I gave up that scandal broth years ago, Li Tong. Give it to your boss.”

While I gave the cup of tea to Armindo, Dr. Murray pulled from his leather bag a flask of brandy and a glass. He polished the glass with a small towel then carefully poured the brandy. “Soaked to the bone, I am, Li Tong, but my tongue feels like the skin of a dried shark; a most unpleasant sensation that I shall endeavor to remedy immediately.”

He held up the glass. “To those dear friends who refuse nothing: the gallows and the sea.”

He drank it down greedily and cleared his throat, then looked about for a spittoon and I quickly moved the spittoon closer to his feet. Dr. Murray expectorated into the spittoon, then primly wiped his mouth with the same towel he had used to wipe his glass.

Armindo’s anger was unabated. “The whole blooming lot of them get the mulligrubs from their own addle-pated stupidity and some beetle-browed emigration agent relands my pork!”

“Be that as it may, as your designated ship surgeon, I concurred that we have no choice but to replace the pork or else-

“Replace thirty casks of pork!? Over my dead body! You can doctor it up by runnin' pickles over it. That'll take care of the bloody maggots.”

“Temporarily.”

“Long enough until we get out to sea!”

Armindo placed his face close to Dr. Murray’s and spoke in a threatening manner. “You best not be forgettin' you work for me, Doctor Murray.”

Dr. Murray leaned back in his chair, the fingers of one hand clutching his glass and the fingers of the other leisurely tracing the initials engraved in his walking cane. “My dear Armindo, I...never...forget I work for you. And you should never forget that without my attestation as to the good health of the coolies, you don't receive permission to sail.”

Armindo stared at him for several seconds, angrily drank some tea, then stared into his cup. “Strong taste, this. This Hyson?”

“Yes, sir.”

Dr. Murray leaned close to Armindo’s cup and inhaled deeply through his nostrils. “Shade of primrose and a brisk, agreeable flavor. Just what I used to drink before I gave up tea in favor of something a bit more fortifying to my system.”

Armindo stared into his cup suspiciously. “Scarcely any color at all.”

“My dear, Armindo, many of China’s finest teas barely color the water.”

“Aye, some do not. And many aren’t teas at all.”

“True, if anyone knows how to pull the wool over a tea drinker’s eyes it is the Chinamen. They give the poorest quality tea to the Manchus because the Manchus add milk, and in restaurants serve rotgut known as ‘foreign-devil’ tea to us because they think we would not know a fine quality tea if it bit us on our behinds.”

Armindo continued to stare at me. “Is that a fact?”

Dr. Murray continued on. “Indeed, sir. Of course, such chicanery is not limited to transactions in tea. Ducks being weighed by the pound, I will not deign to describe the manner in which pebbles are shoved down the poor birds’ gullets to cheat the foreign housewife. But with tea their manner is far more subtle.”

Armindo’s stare never wavered. “Aye. I’ve heard plenty of gup about how John Chinaman adulterates the tea and makes a profit while passing off sloe or ash as tea leaves. And of course he is clever enough to add Prussian blue and other trickery to the coloring.”

Dr. Murray ran one chubby hand through the white hair of his ring beard, looking from Armindo to me and back to Armindo. “What the deuce! Surely you are not suggesting that Li Tong is adulterating your tea?”

“I suggest nothing. But I did once spot such trickery in a barracoon in Macau. The Chinaman that done it got himself shipped out along with the rest.” Armindo turned to me. “Li Tong, pour this water out of the pot and get me a plate.”

I did as he asked. During the time I was in the tiny makeshift kitchen, Dr. Murray did not say a word. I think he understood that Armindo now suspected me of substituting poor quality tea and selling the better grade for profit. It was not uncommon among my people to do so.

Armindo spoke as he carefully removed the leaves from the kettle and arranged them on the plate. “Our bill for tea has doubled since the arrival of our young friend here. Did you know that, Dr. Murray?”

“Well, of course it has; it has everywhere in southern China and the port cities. The Taiping rebels have seized the tea growing provinces and blockaded the trading routes.”

Armindo stared at the leaves. “Aye, that they have.”

We all stared at the leaves for nearly half a minute in silence. The only sounds in the barracoon were the hawking and spitting of the coolies and the guards and the creaks of the roof and walls in protest of the wind’s fury.

Finally, Dr. Murray spoke. “And just what are you hoping to discover, sir?”

“If the tea is genuine, the leaves will retain their color. If they’re sloe or ash or something else, the false coloring will be carried off in the water. And these leaves will be black.”

Another minute went by. I had done nothing wrong, but I had no idea if that could be proved to Armindo’s satisfaction. I knew it was absurd but as each second passed I felt a guilt rise up in me, as if I had something to confess. I knew it was my own weak nature and Armindo’s strong character which made me feel that way. My nerves were being strained as if I were about to be found guilty of a crime. And I think at that moment to please Armindo I would have confessed to that which I had not done.

As we would soon be examining coolies, I thought I should use the time to nib the quills, but the quill needs to be held as steadily as possible and I was afraid my hands might shake exposing my anxiety. And so I sat and stared at the leaves, knowing my future depended on their ability to retain their color.And t

he leaves did retain their color. Dr. Murray turned to Armindo. “Satisfied?”Armindo nodded. “More tea if you please, Li Tong.”

“Yes, sir.”

His

anger was once again focused on the demands of the emigration agent. “Replace the pork?! Next they'll be demandin' we provide every Chinaman that goes on board with his own concubine!”Dr. Murray reached over and popped a lichee into his mouth. “An interesting thought. But I dare say we may have some trouble with this particular agent.”

“I never met an emigration agent that a stack of silver dollars couldn't buy.”

“This one-“

“This one won't be any different. One way or another, I always bring them to their bearings. And what about Captain Elliott? Did he say the ship is ready to sail?”

“Oh, yes. The clipper is all shipshape and Bristol fashion. The ship isn't the problem. It's the acting harbour master. Elliott's on his way over with him now.”

“Doesn't he know the arrangement we had with Nicholson?”

“We'll soon find out. And, if I were you, I'd cut that Chinaman down and get him out of sight.

“What the bloody hell for?!

“Because the acting harbour master is a fellow named James Turner and I heard when he was at Ningpo he was the sort who worried about how Chinamen are treated.

“Turner. Aye. I know that name. Damn his eyes! Li-tong! Get that Chinaman untied and put him with the others. And get Ah-fuk over here.”

I motioned to some guards to untie the coolie, hoping the man was still alive, and walked into the darkness to a group of Chinese crimps and guards absorbed in a game of dice. I looked them over but could not find the one I wanted. “Where is Ah-fuk?”

One of the men pointed to a sleeping figure, bundled up childlike inside a worn wool blanket. At the center of the slate grey blanket I could make out the black letters USM. I had heard Ah-fuk boast of having snatched it on the streets of Hong Kong from a drunken American marine. I walked over to him, leaned over near his ear and lowered my voice. “Ah-fuk...Ah-fuk! Wake up! Armindo wants you.”

He rolled over and grunted. A pair of dice fell from his sleeve to the floor: The red aces seemed almost to glow in the semi-darkness like a tiny pair of angry eyes. Ah-fuk was one of the most repulsive looking men I knew and on occasion when speaking with him I had been unable to repress a shudder.

He had prominent, feral eyes set into a thin dark lupine face and even his most relaxed expression seemed to suggest that sudden violence was just below the surface. On the orders of a magistrate, part of his upper lip had been cut away. It was the Manchu government’s way of discouraging inveterate opium smokers from continuing with their habit. In addition to disfiguring his face, the punishment had also affected his speech. He compensated by raising his upper lip when he spoke and moving his lips in an exaggerated way.

He had also once contracted smallpox and his deeply pitted face was what we Chinese call a “chop dollar face,” because the Mexican and Spanish silver dollars introduced by the foreign devils were tested for purity so often by our merchants and vendors that the tiny testing implements left a myriad of small holes on the faces of the dollars.

I knelt beside him, steeled myself to look upon him at such close range, and lowered my voice still more. “Did you take care of that thing we discussed?”

As was his habit, he inhaled noisily and widened his mouth before speaking. His upper lip raised up as if it were some living thing which moved independently of his will. “Don't worry. It is done. But the storm-“

Armindo bellowed out Ah-fuk’s name. “Ah-fuk!”

“The storm what?”

He snatched up the dice and placed them inside his sleeve. “We will talk later.” Before I could pose another question he leapt to his feet and hurried over to Armindo. I followed quickly after him. He placed one fist inside the other as we do in greeting and gave him a slight bow. His long, thin queue hung down his back, its natural hair oil already having stained his tunic.

Armindo eyed him with equal amounts of suspicion and displeasure. “You bring the new coolies?”

“Hab got. First chop coolies. Number one.”

“First chop?! You bracket-faced, buffle-headed loon, half the bloomin' coolies you bring me are so sick they die before they reach Peru. I'm within an ames ace of buyin' all my Chinamen from somebody else.”

Ah-fuk sucked in air then spat out his words. “Ga la! First chop! You looksee! You catchee plenty dolla'!”

“That better be right. Bring 'em out!”

As Ah-fuk went to do as he was told, Armindo sat in a chair beside Dr. Murray. He placed his pistols on the table and wrapped his whip around his wrist. He brought out a snuff box from inside his jacket and smeared a pinch of snuff on his nostrils and sniffed. He sneezed almost immediately.

I quickly brought over a pot of tea, a tray of cups, sheaves of paper, quill pens, an abacus, and an ink container. I sat beside Armindo, using a small knife to sharpen the point of the quill, then dipped the nib into the ink.

Dr. Murray had wanted to change over to steel pens but Armindo insisted we stay with quills. He claimed the steel pens lasted only ten days, that they corroded, that their ink flows poorly and the needle-like nibs scratch the coolie contracts to shreds. And so we continued to use a feather from the wing of a goose as our writing instrument.

The light of an oil lamp reflected on the foolscap and on the barrels of Armindo’s two flintlock pistols lying beside it. And on the cross about Armindo’s neck.

Ah-fuk and his assistants emerged from the darkness with six frightened coolies. They led them out by walking behind them holding their queues. Except for their flimsy loincloths the coolies were naked.

When Armindo nodded, I began speaking in Cantonese to the first of the coolies in the tone of severity expected of me when addressing them. “You! Move about to show the outside barbarians that you are healthy. Otherwise, you will be taken outside and left to starve on the island. And don't think anyone will take you to the mainland. They are too afraid to interfere with the foreign-devil business. So do as I say. Run!..Jump!..Turn!..Duck walk!..Bend over!”

Armindo and Dr. Murray observed closely as the man followed my instructions and ran about and flapped his arms and leapt and stooped and jumped. From the man’s thick muscled legs and the callused raised lumps on his shoulders I guessed that he had made his living as a chair bearer.

Armindo seemed satisfied. “He looks strong enough to me. Have 'im duck walk again.”

“Walk like a duck again! Quickly! Before the foreign-devil is angry!”

The coolie quickly obeyed. Armindo looked toward Dr. Murray who nodded. “Yes, he will do just fine.”

Armindo nodded to me. “All right! Have him sign.”

I employed my quill to make notes on sheets of foolscap before me and noisily slammed beads on my abacus. “Sign the contract.”

The coolie walked forward and I roughly grabbed his finger and pushed it onto an ink pad, then pressed it down onto the contract. I then placed a cord about the coolie’s neck which had a number on a bamboo tag. “This is your number. Number two-nine-zero. When you go on board the black-sided coolie ship, a foreign-devil will call out your number. You will walk forward and he will ask you if you go on the voyage willingly. You say 'yes,' understand? Anyone who says 'no' will be beaten and dragged in the water from the rowboat! You understand?!”

For several moments, the coolie stood transfixed, staring at his blackened finger as if some kind of magical transference had occurred. I saw that he had written the character for “earth” on his palm. I knew some of the coolies did this hoping that it would protect them from becoming seasick. Finally, he nodded.

“Now go upstairs! If you cause trouble you will be whipped and left to hang by your thumbs.”

The coolie quickly climbed the steep, narrow stairs to the cockloft. The second coolie obediently performed in response to the orders. “Run!..Turn! Flap your arms! Bend over!..Jump about while turning!..Duck walk!..Stoop!..Jump about! Quickly! Do not make the foreign-devil angry!...Enough! Spin your queue!..Enough!”

When I saw their nods, I barked orders to the coolie. “Now sign the paper and rejoin the other coolies upstairs!”

Panting heavily, the coolie did as he was told.

The third coolie ran to stand where the other had stood. He too obeyed my orders. “Hurry up! Flap your arms about and run!..All right, now jump up and down!..Now duck walk!..Stoop!..Enough! Now, spin your queue! Quickly, you coffin chisel, or else the red faced barbarians will whip you again!”

As the coolie spun his head sending his queue flying about, I heard the sound of a coin as it was flung against the wall. Ah-fuk walked to the coin and picked it up.

I screamed at the coolie. “Hiding coins in your queue! For that you will be beaten! And lose your queue. All of you had better remember what I told you: If you cause trouble you will be beaten! Go to the back! Wait there!”

Ah-Fuk walked to me while still intently studying the coin. I suspected the man was a triad member and that it was a coin issued by one triad or another. But when I saw what it was, my pulse raced. I turned to Armindo. “This is a coin of the Taiping rebels. Tai ping tien guo. Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace.”

Armindo studied it in silence then rapidly turned it over in between his fingers as a gambler might do.

A nervous tremor had crept into Dr. Murray’s voice. “The rebels are getting stronger all the time. Rumor has it Frederick Ward was killed fighting them at Tse-kie. And now one of the Taiping armies is said to be heading this way."

We all knew what Taiping rebels did to anyone involved in opium or prostitution or in any religion other than their bizarre form of Christianity. Or even to anyone subjecting himself to the Manchu hairstyle. No doubt they would have nothing pleasant in store for anyone involved in the slave trade.

Ah-Fuk had had a narrow escape from them and I could tell he was becoming excited. His men had also grown very quiet. He spoke hastily and his deformed upper lip jumped about. “Plenty piecee bad man Taiping hab got this side, too muchee likee cut throat pidgin."

Armindo spoke softly to Dr. Murray. “Tse-kie is only some ten miles from Ningpo, is it not?”

“Yes. Just a short ride inland. And not that far from here.”

Armindo stared at the coin. “Well, let’s hope if one of their armies is heading this way it’s one of their all-women outfits. I wouldn’t mind a tryst with their so-called silken army. I’ll wager they look right proper flash packets in those silken gowns of theirs.”

“Aye, silk they looted from Hangchow. But I hear they fight more bravely than the men.”

Armindo slapped the coin on the table. He raised his voice. “Well, Dr. Murray, I have no interest in rumors. Have our best men question that man carefully and thoroughly. Now bring in the next coolie.”

Ah-Fuk took a step toward Armindo. “But what if-”

“Be quiet, you bullet-headed fool! We’ve all smelt powder and heard ball. If the bloody long-hairs want a fight, they’ll find one waiting for them here. Now bring in the next man.”

Ah-Fuk’s men took the coolie away to be tortured for information. Ah-fuk thrust the fourth man forward. He was squat and dark and middle-aged. He followed my orders as I shouted. “Jump! Squat! Flap your arms...Duck walk...Now, the other way.”

I looked to Armindo and Dr. Murray for instructions. Both men nodded their approval.

“Enough! You are number two-nine-one. You heard what I said. When you are asked on board the barbarian devil ship if you want to go, you say, 'Yes.' Otherwise you will regret it.” The coolie walked forward and stood quietly while I placed the cord with the number around his neck. When he spoke it was directly to me. “Please, I am a charcoal seller. Some men told me where I might find better employment. But when I went with them I was gagged and tied and taken here.”

“Be quiet!” I did not want him to get into any trouble by protesting so I grabbed his arm just above some angry red burns. “You were burned by joss-sticks before. Do not cause more trouble or you will receive even worse! Here! Sign!”

I dipped his finger in ink and pressed it to the contract. The man fixed his eyes on mine and spoke quietly but with resolution. “I would rather die than go on the outside barbarian ship. Others say it has no shrine to the heavenly goddess. How will it find its way in a storm?”

“Be quiet! Go up the stairs and remain there. Quickly!”

He turned and moved toward the stairs, then slowly mounted each step as a man might were he being led to the gallows.

I was angry at myself for allowing his pleading eyes to move me. I screamed at the next man. “Jump! Run! Squat!..Duck walk and flap your arms!”

The man’s teeth were discolored and his cheeks sunken. His withered skin had a chalky paleness, and he seemed short of breath. It was clear to me he was an opium smoker. While the emaciated coolie leapt and duck-walked and flapped his spindly arms, he began to cough and stumble. Dr. Murray rose and looked into his eyes and mouth and ran his hands along the man's body as if checking the health of an animal.

Dr. Murray spoke while he looked inside the man’s eyes. “This man is sick.”

Ah-fuk was quick to deny it. He inhaled loudly and spat out his denial: “No sick. It too much laining. Him hab cold.”

“No, not a cold. The man's at death's door.”

Armindo stood up so quickly his wooden chair toppled over. He walked to Ah-fuk and brushed past Dr. Murray. He slapped Ah-fuk’s face with the back of his hand. Ah-fuk’s hand darted to the fan tucked in at the back of his neck which was actually a sheath for a knife but then thought better of it.

“You no 'cassion makee so-fashion!”

“I warned you not to bring me anymore like that.”

Ah-fuk snatched his queue in his right hand and twisted it from left to right. "You too muchee saucy, galaw!"

“One more time and I'll find another crimp. You savvy?!”

“...I savvy.”

“Take him out.”

Dr. Murray protested. “He'll die out there.”

“He'll die where he's goin', so what's the bloody difference?”

Dr. Murray reached for his doctor's bag. “I might be able to save him with-“

“He'd be shark meat before we were three days sail out of Swatow.” Armindo turned to the crimps. “Take 'im out!”

As the man was being bundled out, he had almost reached the door when he began shouting to the other coolies. “At least I will die with my bones in Chinese soil! You are not going to the Gold Country. You are going to hell! Escape while you can!”

Armindo turned to me. “What did he say?”

“He...he just said his life is hell and he knows he will die soon.”

“That's it?”

“Yes.”

Armindo’s movement was so fast and agile, I never really saw it. He grabbed me behind my head, pulling it down by my queue, forcing my face very close to the flame of a candle. I was very much afraid.

“The missionaries taught you good English. And you're smart. And you keep good books. All that makes you useful to me. And the Spaniards say even the lie that lasts only half an hour is worth telling. And that may be. But, so help me God, you lie to me one more time, and I'll ship you out on the next coolie ship! You savvy?”

“I savvy! I savvy!”

“Now. What did he say?”

“He...he told these men they are not going to the Gold Country. They are going to hell and they should try to escape.”

Armindo finally released me from his grip. “That's better.” He turned to the crimps. “Bring him back.”

The guards force-marched the coolie to stand in front of Armindo. Armindo picked up his whip and stared at the coolie. He started to speak then seemed to change his mind about something, then put the whip down and picked up a pistol. “Ask him if he's afraid to die.”

“The foreign-devil wants to know if you are afraid to die.”

“The next world will be much better than this. My spirit will rise to the Jade Heaven in the Western Paradise. I will be with the immortals. These foreign barbarians are like the silkworms which blight our mulberry leaves. Heaven will not endure men such as these; and you - for helping such men - you will go to the Land of the Yellow Springs!” When he had finished speaking he was breathing in quick, shallow breaths and his sunken cheeks quivered.

“He says the next world will be better. That you are like silkworms destroying the mulberry leaves. And he damns me for helping foreigners.”

“But is he afraid to die?”

“He says he is not.”

Armindo stared at the coolie for several moments, then slowly stood up. “A man who's not afraid to die deserves a chance to cheat death.”

He moved one of his flintlock pistols closer to the coolie and placed the other near himself on the table. “Tell him the pistols are loaded. If he can kill me I order that he be let go.”

Dr. Murray stirred in his chair. “Armindo, what-“

“And returned to the mainland. Unharmed.”

“Armindo-“

“Damn your eyes! Clap a stopper on your tongue!”

“The foreign-devil has told the others that if you can kill him, you are free to go. No one will harm you.”

The coolie stared at the flintlock nearest him. His breathing was still labored but he seemed inwardly calm. There was no sound in the room except for a few moans in the darkness from Chinese who had been whipped or beaten. And the sound of a whip on the back of the coolie who had hidden the rebel coin in his queue. Armindo stepped away from the table, tempting the coolie. He spoke almost in a whisper. “Go ahead. Grab it. Maybe you're faster than me.”

The coolie’s large eyes stared at the weapon from above his emaciated cheeks. After several seconds he made a sudden grab for the pistol. The weapon seemed unnaturally large in his bony hand but he pointed it at Armindo. Armindo made no attempt to reach the flintlock nearest him. The coolie hesitated then pulled the trigger. The powder in the pan flashed and smoked. The coolie stared at the flintlock, then lowered it.

“Well, look at that. The Chinaman had the nerve, after all. The bleedin’ powder must be damp. When that happens, powder only flashes. A flash in the pan.”

He walked forward and reached for the other pistol. “This one, though, I expect the rain didn't get to quite so much.”

“You are a turtle's egg!”

“What'd he say?”

“He said you are the egg of a turtle.”

“What the bloody hell's that mean?”

“The turtle lays its eggs, then leaves. The turtle baby...does not savvy who is its baba.”

Armindo threw his head back and laughed uproariously. “Do you hear that, Dr. Murray? The Chinaman called me a love-begotten child! A bastard!”

Dr. Murray chuckled but I could tell he was as uneasy with what was happening as I was. He fingered the head of his walking cane nervously.

“Li-tong, tell him I’m not going to kill him.”

“You’re not?”

“Hell, no.”

Armindo suddenly threw the pistol to me. I fumbled with it, but managed to hold on. I stared at Armindo.

“You are.”

“...I cannot kill someone.”

“Sure you can. Killing a man is just a question of what’s in it for you. In this case, it’s your life or his. You don’t take his, I’ll take yours.”

“Armindo, there’s no call to-”

“Shut your trap, Dr. Murray!” He turned to glare at me. “I’ll count to ten. You use that barking iron on him, or, by Christ, I’ll load this one and use it on you. One! Two! Three! Four!”

I hesitated and then pointed the pistol at the coolie. My hand was shaking badly.

“Five! Six!”

“I cannot kill someone!”

“You’ve been killing men for years! Helping me send them to the Chinchas to work themselves to death. A man can’t touch pitch and not be defiled. We’re one and the same kind, Li Tong. Haven’t you figured that out yet?” He took a step closer to me and stared into my eyes. “What is it? You can send men to a slow death but you can’t give a brave man a quick one?”

I could feel myself beginning to shake. My entire body was covered with perspiration. “Please, I-“

“Seven! Eight!”

I pulled back the cock from the safety position.

“Nine!”

Bones of the China: Part 2 of 4