Bones of the Chinaman

(continues)

Part 2 of 4

I pulled the trigger. There was another flash in the pan. The smoke rose to my eyes and my tears began. I stared at the pistol, then, my hand still shaking, slowly handed it to Armindo. Or rather I held it out and he took it from me.

“Well, I’ll be damned! You see that, Dr. Murray? Our interpreter has what it takes to kill another man. That beats the Dutch and the Dutch beats the devil! I better bear that in mind.”

I stood without moving staring at my shaking hand.

“Li-Tong, Get me the cleanin’ oil! Ah-fuk! This heathen celestial has guts. Have your men take him the hell out of here. Into town. No harm is to come to him.”

Armindo reached into his pocket and pulled out several Mexican dollars. He handed the dollars to the surprised coolie. Armindo stared at the coolie but spoke to Ah-fuk. “And I better not find out later that these dollars Mex found their way into your pocket. Savvy?”

“I savvy.”

The coolie stared at the coins then threw them to the floor. He spat out his words in Cantonese. “I will not take

devil-faced money."In the silence that followed, one of the crimps quickly retrieved the coins. Armindo stared at me. “Li-tong?”

“He says he will not take your devil-faced money.”

Armindo took a step forward, standing just inches away from the coolie, staring into his eyes. I was certain he was about to use his knife. Instead, he reached out and took the coins from the crimp. “Tell him he can use the devil-faced money to buy medicine or, if he likes, to buy more opium. But if he’s smart, he’ll use it to buy arms; weapons with which he can drive men like me from his land.”

I repeated Armindo’s message in Cantonese. Armindo held out his hand, palm up. The coolie looked at the coins, then reached over and took them. They disappeared inside his sleeve.

“Now escort him into town.”

Ah-fuk barked orders to his assistants. They took the man to the door. Armindo sat down. I handed him the gun-cleaning oil and brushes. He began cleaning and reloading his flintlocks. I stared at the pistols as a man might stare at something that has taught him something ugly about himself. Something that will haunt him in his dreams.

Dr. Murray quickly poured himself a drink from his flask and drank it down. He spoke once he was able to bring his coughing under control. “No guarantee his pistol's powder was too damp to fire. You took a hell of a chance.”

“We take a hell of a chance the day we're born.”

“I never thought I’d live to see the day you be giving silver to John Chinaman. I thought he was a goner for sure.”

“Why kill one of my own kind? That Chinaman has as much hate inside him as me. He knew what he was made of; Li Tong here is just finding out what he’s made of, isn’t that right, Li Tong?”

I heard Armindo’s voice as if it were a sound far away. I could not take my eyes from the pistols. Suddenly, I needed to relieve myself urgently. I could hear subdued laughter behind me as I grabbed a whale oil lamp and quickly strode in the direction of the privy. I moved rapidly but carried the lamp carefully as its shade was of blown glass and my hand was far from steady.

For those of us who were not coolie slaves the recess which served as our privy was at the southeastern corner of the barracoon. I set the lamp on a shelf beside a brass censer with burning incense, shoved a bamboo bar from its latches, and pushed the wooden door open. Although the two tiny windows were double barred, the cold weather shutters had been breached by the storm and both wind and rain were penetrating the alcove.

In his attempt to conceal odors, Armindo had imported workers from Canton to improve the sanitation. Inside the privy the rammed earth of the barracoon gave way to unglazed brown tiles. They had erected a drain of inferior blue brick set in coarse mortar. It led from the privy under the wall and continued along an outside path under slabs of granite. But the storm had clogged the drain and it was completely backed up with foul matter and filth rendering the stench overpowering. The clay pot in the corner had yet to be emptied and its rattan cover had been blown aside adding to the offensive emanations.

But I had almost killed a man and I was too lost inside my own nightmarish introspection to think of odors. I was sweating profusely and I stank. When I had finished my business and felt fairly certain I was not going to throw up, I stood up. I threw water onto my face, and used a soiled towel to dry off.

When I emerged from the privy, the crimps were opening the door to escort the coolie out, and, above the roar of the wind and rain, we could hear the sounds of horns, cymbals and drums.

Armindo stared toward the front door. “What in damnation is that infernal noise?”

Dr. Murray poured himself another drink. “Tonight'll be a full moon. The seventh of the year. The Chinamen believe hell opens up and the spirits of the dead are allowed to visit earth. Starting tonight. That's their welcome.” Then he turned to me. “That right, Li Tong?”

“Yes. The spirits are allowed to stay for one month. But many of these spirits are the restless ones.”

Armindo looked interested but suspicious. “Why restless?” “Because they died violently and cannot rest until the person responsible is punished.”

“Just like a Chinaman to risk his life in a storm to welcome dead spirits.”

Ah-fuk appeared suddenly from the darkness of the interior. “Boy say yes, he spy looksee foreign-devil for Taiping. But Taiping cannot come this side. Hab too muchee afraid devil cannon.”

Armindo seemed almost depressed by the news. I had heard him speak in admiration of the bravery of the Taipings compared with the incompetence of the Manchus. I really think he had wanted a chance to engage them in battle. “All right, put him with the other coolies.”

Dr. Murray held out his glass, and spoke his toast, then gulped his brandy down. “A toast to the Taipings! All hands forward to splice the main brace!”

Armindo eyed him in disapproval. His face was flushed and his eyes were merry with drink. “Easy on that! I don't want you full as a fiddler's bitch before Turner even gets here.”

He saluted him with his glass. “Aye, aye, sir! But this storm reminds me of action I was in on the coast of Chusan during the China War. Hell of a storm then, too.”

“Are we in for another of your stories then, Doctor Murray?”

In response to Armindo’s question, Dr. Murray simply raised his walking stick as if to say it would not be a long one. “I had been sent ashore to find some provisions. We were at war with the Chinese in the north but the southerners would ready enough sell us what they could for Spanish dollars. What we really needed was eggs. But I was having a devil of a time making myself understood to the villagers. So I took my handkerchief out of my pocket like this, and rolled it up into a ball. Then I stooped down like this, held the handkerchief down here, then made like a chicken laying an egg.” Dr. Murray did a kind of duck walk of his own for several steps before nearly toppling over.” He raised his voice to a high pitch. “Cockadoodledo!”

He looked so ridiculous I couldn’t help but laugh. Even Armindo joined in. When I could stop laughing long enough to ask a question, I said, “And they understood?”

Dr. Murray climbed back up into his chair. “Oh, yes. And once they stopped laughing, they rounded up all the eggs we needed.”

The levity was quickly dispelled when Armindo turned to Ah-fuk. “Bring the last one.”

The last of the coolies was a young man. His clothes and manner suggested he was from a higher class than the others. His hairline was shaved in the manner of a scholar or man-about-town. Unlike the other coolies, his queue was loosely plaited and black cord tassels had been affixed to it to give the appearance of greater length. The border of his crown had been neatly shaved. He seemed unable to cease sobbing.

Dr. Murray’s speech had become slightly slurred. “Here, here, lad. The more you cry, the less you'll piss!

Armindo slammed his whip onto the table. “Tell the Chinaman to shut his bone-box or he'll end up in 'is eternity box.

“Keep quiet or the foreign-devil will make it worse for you!

“My father was taken by crimps and sent on board a foreign ship. He never returned. My mother has no other sons. If I am taken abroad who will burn incense before our ancestral shrine?

Armindo was growing impatient. “What's his problem?

“He says he is his mother's only son. If he is sent away who will carry out his duties to his ancestors?

“Bad luck, that. But if he don't shut his rice-trap, she won't have any son!

Prodded by Ah-fuk’s threatening gestures the coolie carried out my orders. “Run! Flap your arms! Faster!..Duck walk!..Bend over! Squat!..Enough! Sign the contract!”

The man looked at the contract. “I can't read it in this poor light.

“You don't have to read it! Just sign it!”

I roughly pressed his finger down on the contract and Ah-fuk led him away.

I was about to reenter the kitchen alcove when I heard more pounding at the door. The guards held the door in place long enough to allow two men to enter: The American clipper ship captain and the acting British harbour master.

The sounds of the storm seemed more insistent than before. If anything, the squall seemed to be worsening.

The men removed their flat-brimmed rain hats and dripping pea jackets while adjusting their eyes to the dim interior light. As I placed their jackets and hats on wall pegs, they walked to the table.

Armindo abruptly shoved a crimp off a chair to make room for the acting harbour master. The captain remained standing nearby.

Captain Elliot was a tall, distinguished looking man and his sea-beaten, light brown face was framed by the whitest of mutton-chop whiskers. His bottle green eyes matched the shade of his guernsey which was always neatly tucked inside his bell-bottomed duck trousers. I seldom saw him without his short nut brown pipe pressed to his thick lips.

The first impression I had of him was on my second day of work when he was standing within an area of darkness inside the barracoon. He was wearing his black beaver overcoat and black boots and holding an oil lamp which cast a strange yellowish glow across his face. I thought at first he was some kind of demoniacal vision and I jumped at the site of him. He threw his head back and roared with laughter.

Armindo pulled out a cane chair and slid it across the floor. “Anchor your ass to a chair, Mr. Turner. I'm Armindo DaCruz. You already know Dr. Murray. Li Tong, pour the gentleman some tea.”

The acting harbour master was plump and squat with an abundance of curly black hair, well trimmed black sideburns and a short bristly mustache. His pale, unnatural, almost ivory, complexion immediately reminded me of a type of bean curd my grandmother prepared at festivals. He wore a coarse blue jacket with black horn buttons, too short for his body and bell-bottomed duck trousers which had probably fit him perfectly when, as a much younger man, he had bought them. He seemed a man who, in normal times, would not be hesitant in his manner or vague in his demands. But whatever he had witnessed on his way to the barracoon had obviously disoriented him. He did not immediately respond to Armindo but, seemingly stunned by what he had seen, silently rubbed his shoulder.Armindo studied him with genuine concern. “You hurt?”

“I've never seen anything like it.”

“Like what, Mr. Turner?”

“All the sand is being blown away by the storm and the bones of the Chinamen are coming to the surface. They're swirling about like leaves. One of them hit my shoulder. It felt as if I'd been clubbed.”

“Let Dr. Murray have a look at your-“

“Some of the poor buggers never had a coffin to begin with. Some were never even buried, just left to rot. And the storm has exposed their corpses and dead men are dancing about as if the wind were blowing life into them. The dogs and swine got hold of some. I saw a dog with the bones of a human hand in his mouth. And the way some of the more recently buried were being blown along the ground, the expressions on their faces; it almost looked like...like-“

“White birch twigs.” Mr. Turner’s mood seemed to have affected Dr. Murray. “That's what they looked like to me. I never saw so many-“

The guards playing dice suddenly grew loud and argumentative. Armindo took a step in their direction. “Goddamn ye! Stop your heathen gabble or I'll cut your heathen tongues out! You got nothing better to do, go check the Chinamen to see what they're hiding in their pigtails. And check their mouths and assholes!”

I knew they understood his meaning but I yelled at them in Cantonese as well. “Quiet down and earn your pay! Inspect the Coolies closely for anything hidden! Queues! Mouths! Ears! Assholes!”

The crimps moved off into the darkness to carry out the order. Meanwhile, the Captain tamped down the tobacco in the bole of his corncob pipe prior to lighting it.

Dr. Murray held up his flask. “Right about now a smart nip of brandy and water is what I would recommend for the both of us, sir.”

“I thank you sir, no, but I will take the tea.” Turner took a sip of tea and stared into the cup.

“The wind is blowing them here.”“Armindo narrowed his eyes. “Blowin' what here?”

“The bones of the Chinamen. They're being blown about like chain-shot. And there's a flotilla of coffins rushing down the river, like some kind of well rehearsed, water-borne procession: each coffin stays perfectly in its place as if it was being expertly guided.”

Armindo tapped the table with his whip. “Dead men at the helms, is it? Sounds much like a well-spun galley yarn to my ears.”

“This is no galley yarn, sir. A devilish night, is what it is.”

“Well, it's some squall, all right. Anyway, do sit down. I'm real sorry to hear about Mr. Nicholson. Cholera, was it?”

Turner sat and looked about as if what he had seen outside was still in his mind more real than what was inside the barracoon. He turned to Armindo and nodded. “He lingered between wind and water for a few days but then he passed on.”

“He was a fine harbour master. Fine as they come.”

“Yes. He was.”

“Many fine men I've known have slipped their cables in Swatow or Macau, Mr. Turner. My own brother lies in Hong Kong's Colonial Cemetery.”

“Colonial fever?”

“Bloody pirates tortured him and chopped his head off to get the reward for foreign devils' heads. One hundred silver dollars. Paid by the viceroy of Canton hisself. One day I hope to meet up with that heathen.” For just a moment, I felt Armindo’s eyes bore into mine with his venomous hatred for all Chinese. “Until then, I do what I can to pay them back.”

Armindo suddenly noticed the Captain still standing and positioned a chair for him. “Captain! Bring your ass to an anchor and tell me the clipper is ready to sail.”

Captain Elliot remained standing and circled his pipe with a friction match. The flame dipped down, sparks flew and smoke wreaths curled about his head. “Aye, the clipper is as sweet as a nut and clean as a dairy, but she won't be sailin' anywhere just yet.”

“Why in blazes not?!

“You better ask Mr. Turner.”

“You're not ready to sail.”

“Not ready?! We loaded rice, salt, tea, biscuit, firewood, lard, tobacco-“

“Your provisions you can discuss with the emigration agent. I'm talking about the windsails.”

“We've fixed up a windsail!”

“The new regulations specify that there should be a windsail for every hatchway; and scuttles and air funnels.”

“Bloody hell!”

“And twelve feet per coolie is the minimum. As you're planning on placing three hundred coolies on board, that means each coolie will get only about eight feet.”

“We housed over the upper deck from the mizzen forward! That way we can carry nearly as many coolies on the upper deck as on the 'tween deck.”

“I already took that into account, Mr. DaCruz.”

“So what are you sayin'?”

“I'm afraid you'll just have to ship fewer coolies.”

“And how am I supposed to make a profit if I ship coolies below cost?”

“Coolies are very much in demand in the Chinchas, are they not, sir? For mining?”

“Not mining. Digging! The islands are covered with guano. Bird shit.”

Dr. Murray spat into the spittoon. “They say it's thirty times more effective than ordinary manure. The best fertilizer for agriculture ever known. And it's makin' men wealthy beyond their dreams!”

Mr. Turner calmly sipped his tea. “Well, then, I would think that at the going rate men are willing to pay for them, three hundred coolies would bring you a fine profit.”

“Aye. That they would if I didn't have to allow for twenty percent dyin' on the way there.”

“Twenty percent!”

“Aye. And that's only if all goes well: No diseases. You explain it to him, Dr. Murray. He's new here.”

“Very well, sir. My last voyage from Swatow was to Havana. The coolies weren't used to the heat of the Tropics. And in the ship's close confinement they grew weak. Then apathetic. Then they started to cough. Their skin became red and blotched. Then the eye diseases started spreading. When I saw the fever and nausea I knew the intestinal worms had arrived. And the worms started the diarrhea. And the diarrhea became dysentery.”

“Didn't you disinfect?”

“We did. And when we had nothing left to disinfect with we fumigated the 'tween-decks with boiling pitch. But nothing slowed it. There wasn't anything I could do for the poor bastards. By the time they died they were just bones covered by loose folds of shriveled skin.”

“How many did you lose?”

“One hundred and thirty-four Chinamen.”

“My God. So what did you do with them?”

“What we always do. When a man died we sewed him up in a rice sack and tossed him overboard. Why do you think sharks follow ships in the coolie trade, Mr. Turner?”

Armindo again rapped the table with his whip. “Aye! John Chinaman loves the taste of soup with shark fins and the sharks love the taste of John Chinaman!”

I noticed Turner did not join in the laughter. “I think I'll have that drink now.” He took the glass offered by Dr. Murray but ignored his toast.

“Never dance with the mate when you can dance with the captain!”

Dr. Murray gulped his down. Mr. Turner swigged some brandy down, then returned the empty glass to the table. When it started to fall he caught it and placed it upside down. The Captain immediately walked over and set the glass upright. There was genuine anger in his voice. “Never place anything upside down before a voyage, sir! It suggests a ship capsizing.”

“I beg your pardon. I didn't-“

Armindo continued on impatiently. “So you can understand, sir, why I have to ship at least three hundred coolies just to ensure a small profit.”

“Well, I'm sorry, but I can't issue port clearance papers the way things are now.”

Armindo rose and gestured for Mr. Turner to follow him a few steps into the darkness. They stood in profile just inside the reach of a flickering candle which bathed their faces in an unsteady golden light. I could not help but stare at the contrast between the light bean curd complexion of the acting harbor master and the dark, leathery skin of Armindo. Curls of smoke from the Captain’s pipe drifted lazily across their glowing faces the way passing clouds partly obscure the moon. They lowered their voices but I could still make out their conversation.

“Didn't Mr. Nicholson explain about things? How they work, I mean.”

“I know about your arrangement with Mr. Nicholson. Two shillings a head, wasn't it?”

“Aye. A florin for each coolie who leaves Swatow on any ship I charter. He got paid whether they arrived alive or not. Peru or Havana - destination made no difference.”

“Well, I'll tell you, sir. Ever since the British passed the Chinese Passenger Act, things have gotten tight. A harbour master looking the other way these days is taking a great risk.”

“And just what rate per coolie might make it worth the risk, Mr. Turner?”

“...One crown per man.”

“A crown! Before I'll pay you five shillings a man I might just as well scuttle the ship and sink 'er to the bottom of the harbour.”

I saw something flash in the dark and I realized Turner was looking at his pocket watch. He too knew how to play the game. “Well, I wish I could have been of more help to you, Mr. DaCruz, but Hong Kong's Governor Bowring is dead set against the coolie trade, and he's not a man to-“

“Wait! I'll give you a half-crown per man. That's the best I can do. Bloody Chinese Passenger Act or no bloody Chinese Passenger Act.”

“I won't risk the wrath of Sir John Bowring for a farthing less than three shillings per man.”

Armindo appeared about to explode then with what must have been an enormous effort managed to calm himself. “All right. No point in going to loggerheads over half a shilling. It's done.”

“Very well, sir. You have my word. Once I've received the specified sum, you'll have your port clearance papers. You do understand you'll still have to deal with the emigration agent.”

Don't worry about him. When he smells the silver, I imagine he'll pocket his pride just as fast as you did yours - in a pig's whisper.

Turner gave Armindo an icy “Good day to you, sir,” then turned abruptly and walked to the door. Armindo imitated an elaborate gentleman's bow. “And a good day to you, sir.”

Dr. Murray held up his flask. “Hell of a storm out there, Mr. Turner. Care to rinse your ivories one more time before you go?”

Turner continued on as if he hadn’t heard. I held his hat and coat out to him. He quickly put them on, bundled himself up as best he could, then headed for the door. I opened it for him and immediately found myself struggling with the angry wind.

Mr. Turner raised his voice. “Thank you, sir, I think not.”

“As you like, sir. But here's to the well wearing of your muff.”

Dr. Murray gulped his drink. As Turner left, deafening gusts of wind and rain seemed almost desperate to make their way inside the barracoon. I had to call to a crimp to aid me in pushing the door shut.

Armindo made an even more elaborate bow in the direction of the closed door. “And may it be a good day when the next bit o' muslin you encounter leaves you pissin' pins and needles.”

Dr. Murray waved a plump finger at him. “Now, Armindo, you really shouldn't be wishin' the French disease on anyone - not even harbour masters.”

Armindo’s fingers caressed his chin and down along his neck. “Li Tong, I think it’s time I had a shave.”

I have often wondered if the day – and my life – would have ended differently had Armindo not needed a shave that day. But I already had hot water boiling in the kettle so I quickly set out the porcelain basin and poured the water in.

Armindo stripped to his waist and lathered his face and neck. I saw again the puckered scar of a bullet that had passed through his shoulder. While waiting for the lather to take effect, Armindo cursed the new price per coolie then briefly discussed the route of the Captain’s ship to the Chincha Islands, calculating provisions based on expected number of days at sea minus the expected number of coolie deaths at sea.

He then propped up a copper-backed mirror and, while standing, used his straight razor to begin shaving himself. The razors of the foreign-devils are much longer than ours and narrower in the blade and when I stared at it, Armindo pretended to hand it to me and joked that someday I would no doubt cut his throat with it so why not then. When he saw how horrified I was, he roared with laughter and snatched it back.

But as the blade touched his skin again, he let out an oath and I saw a trace of blood. “Li Tong, this blade isn’t sharp. Hang the strop.”

I did as he requested.

Dr. Murray got up rather unsteadily, still holding his bottle, and walked about, studying the beams. He began humming and then softly singing a sea chantey. “Let go the reefy tackle! Reef tackle! Reef tackle! Let go the reefy tackle! For my britches are yammed!” Captain Elliott smiled and then joined in as well. “My britches are ya-ammed, my britches are ya-ammed! Let go the reefy tackle for my britches are yammed in the sheetblock!” Soon even Armindo was running his razor back and forth over the strop in time to the music and then he too joined in. “Let go the reefy tackle, reef tackle, reef tackle, let go the reefy tackle, for my britches are yammed! My britches are ya-ammed, my britches are-“

Suddenly Armindo looked up and noticed what Dr. Murray had seen: water dripping down from the ceiling through the cockloft.

“Li Tong! I thought I told you to get a carpenter to fix that.”

“They will not come.”

Armindo studied me quizzically. “Not another yarn made of moonrise, is it, Li Tong?”

Captain Elliott came to my aid. “Carpenters won't come to barracoons anymore. Too many getting shipped out as coolies once their work is done. Some of them won't even board my ship to make repairs.”

Armindo walked toward the drip. “If I had a bloody ladder I’d fix it myself. Bleedin’ downdraft in here is worse than any ship I ever sailed on. And so’s the stench.”

Captain Elliott looked about as if the stench were something visible. “Any barracoon I’ve ever been in has had more of a stench than any ship’s reeking bilges ever did.”

Dr. Murray was in a fine mood and again began to sing, although his song seemed very melancholy to my ears. “The boatman shouts it’s time to part, no longer can we stay-“

Captain Elliott immediately joined in. “T’was then my Imuna caught my heart, how much a glance can say, t’was then my Imuna caught my heart, how much a glance can say.”

The Captain paused to relight his pipe circling the bowl with a friction match then joined in belatedly. “With trembling steps to me she came, farewell she would have cried. But ‘ere her lips the words could frame in half-framed sounds it died. But ‘ere her lips the words could frame in half-framed sounds it died. Through tear-rimmed eyes came looks of love, her arms around me flung.”

I noticed Armindo seemed very moved by these lines. And although he joined in it was as if he were singing from memory of a parting he was seeing immediately before him. His voice was deep and resonate and though I was too embarrassed to say so, I thought it quite beautiful. “As claims the breeze on sighing grief, upon my breast she clung. As claims the breeze on sighing grief, upon my breast she clung. My willing arms embraced the maid, my heart with rapture beat; while she but wept the more and said would we had never met. While she but wept the more and said would we had never met.”

The song was over but Armindo continued on alone, half speaking, half-singing. “while she… but wept the more… and said… would we had nev-“

I saw that Dr. Murray and Captain Elliott were no less surprised than I was at Armindo’s sudden display of emotion. Armindo turned toward them and seemed about to speak but then noticed Ah-Fuk leading the teenaged boy back out toward the table; the boy whose family now had no one to make offerings to their ancestors’ shrine. Ah-fuk held out two coins in his palm and flicked the boy's queue with the other. “Boy hab one topside. One bottomside.”

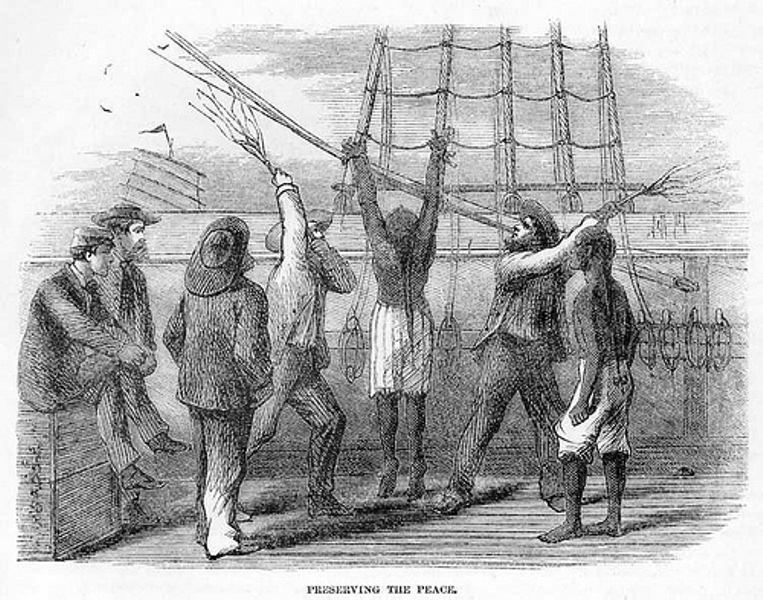

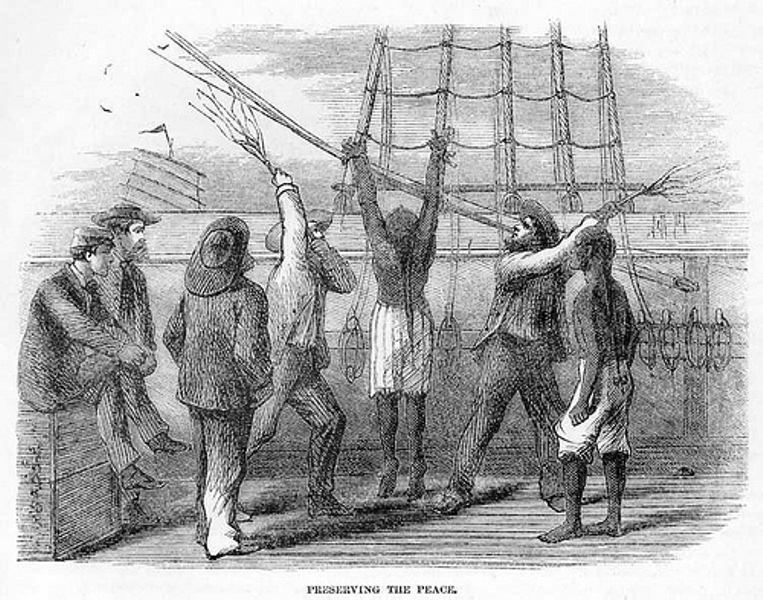

Armindo, now himself again, moved to the boy. “One more Chinaman thinks he can hide money in his pigtail and up 'is arse.” The boy simply stared back at him. For Armindo that was defiance enough. He nodded toward the wall. “All right. Some men just don't understand who's chief cock of the walk in here until I give 'em their red-checkered shirt. Hang him up.”

While the crimps tied the boy’s hands above his head to the wall pegs, Armindo wiped the lather from his face and put his shirt on. He retrieved the whip, stared at it briefly, then walked to a corner of the room and dipped the whip into a bucket of brine. He removed the whip and studied it carefully.

Captain Elliott pressed the stem of his pipe against his thick lower lip. “No call to dip it in brine. He's just a boy.”

Armindo glared at him. “Don't be shovin' your oar into my work, Captain, and I won't shove mine into yours. The salt adds to the pain and there's nothing like pain to make a Chinaman behave.” Armindo walked toward the boy and stood near his back. “And while he's cramped in the hold of the ship on the way to the Chinchas, should anybody whisper in 'is ear about startin' some trouble, this young lout will shake 'is head no and steer clear of trouble. 'Cause he'll remember this!

Armindo flayed the boy’s back and the boy screamed in agony. “And this!”

Armindo continued to whip the boy with all his strength but I had no doubt whatever that during the last sea chantey his mind’s eye had locked on the man responsible for his losing the woman he’d loved. And the memory had unleashed something inside him. Something depraved and demonic. His face was distorted by rage and hate. The boy screamed louder and began writhing and moaning. “And this!”

The whip landed three more times before Captain Elliott took a step forward. “That's enough!”

Armindo lowered his whip and stared at the Captain. He was breathing heavily. “Listen good, Captain. We were both of us born under the gun and educated on the bowsprit. Purser rigged and Parish damned! But the day I left the sea, that's the last day I took an order from another man. You ride the high horse with me one more time, and we'll settle it.”

At the sound of pounding on the door, Armindo hesitated. He nodded to his men to go to the door. They drew their weapons and carefully opened it, struggling to hold it against the force of the storm. Someone rushed in bent low to avoid the wind and rain. The crimps now had great difficulty closing the door. They did not notice that one of the bones of the Chinese dead had blown in after the new arrival.

The figure stood surrounded by Armindo’s men with their weapons drawn. It seemed as if the newcomer was disoriented by the darkness but suddenly spotted the boy tied to the wall pegs and screamed and rushed forward. “Brother! Brother!”

She was just a few feet from her brother when Armindo grabbed her arm and ripped her headscarf off. The woman was young and attractive. I could tell at a glance from her dress that she was from a respectable family. Armindo motioned for me to hold a lantern near her face.

Beneath her long apple green jacket she wore a melon pink tunic with blue trim over broad petticoat trousers of the same design and color. It was tight at the neck but its sleeves were wide. Her face and neck still bore traces of white paste and the rose powder she had applied to her cheeks and eyelids had largely escaped the storm.

Armindo gripped her arms tightly and stared at her. “Well, I'm blowed if it isn't a pretty celestial piece in full feather.”

The woman spat in Armindo’s face and attempted to free herself. Armindo wiped his face with his sleeve and laughed. “And spirited, too!” He ripped her scarf off and ran one hand through her hair. “Beautiful, isn’t it? Soft as sable and black as a raven’s wing.”

The fear that consumed me now was far greater than anything I had felt when dealing with Armindo. I stared at the woman’s beautiful face. “Tiang-si? Is it you?”

It was then that she looked at me closely. “Li Tong? You are with these men?”

“This man is your brother?!”

“Yes.”

“But he should not have been brought here.”

“What do you mean? What do you know of this?”

Armindo scowled. “What the devil is all this?”

“I know this woman.”

“How?”

“In Swatow. At the missionary school, she-“

“What is she to you?”

“She...we were to be married. I wanted her to-“

“He is nothing to me! A man I once knew who turned his back on his own people and went to work for outside barbarians like you. The Li Tong I knew is dead! Now let my brother go!”

“You hear that, doctor? The celestial wench speaks the Queen's English. And from the looks of 'er, I'd say we've got us a lady of quality here, wouldn't you?”

Dr. Murray took a stop closer to look at her. “Yes, well, as Lord Byron so aptly put it: ‘A pretty woman is a welcome guest’ but the Chinese say a woman is as dangerous as smuggled salt, so I think you might want to be-“

“Let my brother go!”

“Well, now, I've got something you want and you” - Armindo looked her up and down – “you've got something I want.”

I took a step toward Armindo. “Please! I will pay you to release her. And her brother. Whatever you ask.”

“Well, I'll be water bewitched and rum begrudged; our heathen friend fancies the wench! Hell, Li Tong, they can both be released. But only if I get what I want from this rigged-out bit of celestial calico.”

Tiang-si continued to struggle. She suddenly got a hand free and ran her nails across Armindo’s face. “Pig seller!”

Armindo clapped a hand over the red streaks along his cheek. “Ow! All right, bitch, it's time to bring you to your bearings.”

He held her wrists and forced her up against her brother’s back. The boy screamed from the pressure on his open cuts. Armindo pressed his body against hers and held his face just inches from hers. “You’ve got a tongue like a discharge of grape and canister at close quarters. But you listen to me, you cockish wench! If your brother makes it to the islands alive, he'll soon wish he hadn't. He'll be diggin' the shit of cormorants, pelicans and gannets for the rest of his bleedin' life. And you know how long that'll be? Maybe two years. Maybe one. No Chinaman ever came back from the Chinchas, you savvy? Ever!”

“Let me go! I don't want-“

She struggled a hand free; he grasped her wrist. “Of course, your brother might do what some others do. He might throw himself over a cliff or bury himself alive in the guano or hide out in a cave until he starves himself to death.”

“Sister, don't give in! Get away! Never mind me! Go!”

“But I promise you this, little lady: while he lives, he suffers. The heat gets up with the sun and the sun on the dew releases the ammonia gas from the guano.”

Suddenly she turned to me. Her dark brown eyes, wide with fear, stared into mine. “Li Tong!”

“And he'll use 'is pickaxe and quarry guano and load it from cliffsides down through chutes and canvas hoses into squareriggers. And he'll do it while standin' in acrid clouds of dust so fine that tiny bits of guano will get into his eyes and nose and lungs until he can't breathe.”

“Li Tong! Help me!”

She struggled and he held her even tighter. She stared straight at me. But Armindo never glanced in my direction. He knew there was not a chance in hell that I would have the guts to try to save her. Not if it meant I would have to face him. He knew me well. I turned away in shame.

“And if he tries to rest, he'll get flogged by the overseers, huge African negroes, blacker than the ace of spades, with cowhide lashes that cut into a man's skin like knives. He'll quarry five tons of guano a day or he won't eat. And no day off. Until he drops. And the turkey buzzards will be wheelin' overhead, waitin' to feast on his corpse! That's your brother's fate. Or not. It's up to you.”

“Sister-“

“Or we could wait for a ship sailing to Cuba where he’ll be sold at public auction and then under the whips and pistols of the negroes and the growls of the bloodhounds he can toil seven days a week, eighteen hours a day and be penned up at night with hundreds just like him.”

“Sister, please don’t-“

Armindo suddenly whirled and, holding her wrists with one hand, brutally whipped the brother with the whip in the other - one stroke. The brother screamed.

“No! Stop! All right! I'll do anything! Don't hurt him! Let him go!”

“We have an understanding, then, right?...Right?!”

Tiang-si nodded.

“Smart girl. Good girl.”

As he attempted to kiss her, she moved her head. He kissed her neck then released her. “Jasmine...Your skin smells of jasmine, did you know that? No wonder Li Tong fancied you. I've occupied a few celestial women in my time but always they was swivel-eyed, bacon-faced strumpets; never a well-rigged China frigate like you. How 'bout it, Dr. Murray? You ever had a celestial flash packet in full feather like this one?”

“Can't say that I have.”

“Damn right you haven't!” Armindo looked her over with pleasure. “Go up into the cockloft, take off your rigging and wait for me. I'll soon have you grinnin' like a basket of chips.”

“I don't understand.”

I was too embarrassed to look at her when I spoke. “Tiang-si. Go upstairs. Take...take off your clothes. Wait there.”

She started to go to the stairs then turned and walked directly to me. “I loved you. Even when you were a boy and you teased me so mercilessly I loved you. And when you were a man and penniless, I loved you even more...now...you disgust me.”

She stared at me until I looked away. She climbed up the stairs and disappeared into the darkness. Armindo walked to the table and placed his pistols on the table. “Stop looking all in the Downs, Li Tong. The ladies take quite a fancy to me once they’ve got to know me. And this one smells sweeter than the sea air off Java when its perfumed with spice trees.” He ran his fingers over his flintlocks. “You'll watch over my barking irons while I'm with the chippy, won't you, Doctor?”

“I will. But I wouldn't be so hasty if I were you.”

“What are you talking about?”

“The way she dresses. Her makeup. Her English. She may have been from Swatow once but not now.”

“What of it?”

“I'd say she's up from Hong Kong. And from the looks of her she's probably the mistress of some English merchant.”

“You sayin' she's got the pox?”

“No, my dear, Armindo, I'm saying that somewhere in the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong, there might well be an English gentleman that would pay a king's ransom to have her back unharmed.”

“...Aye. That he might.”

Captain Elliott tapped the table with the bowl of his pipe. “Aye. Or he might send up well-armed men to get her back by force. And he might have done it already. For all we know-“

Armindo began walking steadily closer to the Captain. “Captain, I have a recollection of tellin' you not to shove your oar into my business, do I not?”

“If she does belong to a Limejuicer in Hong Kong, your playing John-among-the-maids with celestial whores could place us all in danger. Including my ship!”

“Your ship?”

“Aye. I won't stand by while you place my ship in danger of being seized.”

“We have a contract to ship coolies, have we not?”

Captain Elliott stood up. “Damn my toplights, you can keep your coolies. I never did fancy my clipper being used to transport Chinamen to Peru. And guano from Peru to London. Slaves and bird shit! No. I'll find other cargoes for my ship.”

“And what cargoes would those be, Captain?”

“Tea, silks, whatever. Why, in the gold rush days, we-“

Armindo suddenly unleashed his whip, wrapping it around the Captain’s legs, sending him sprawling. Armindo immediately grabbed him up and threw him against the table. As he spoke, he forced the Captain’s head back with the barrel of one of his pistols, its muzzle placed under the Captain’s chin. He cocked the pistol.

“Now you listen to me, Captain. The gold rush days are over. And there's plenty of once-proud clippers beggin' for cargo. The rates for your precious ships have gone to hell in a handbasket and you damn well know it. And your ship is so rotten it's little more than a hulk with canvas and blocks. You can forget about tea and silk. You're bloody lucky to get a cargo of Chinamen and you're gettin' that only because you were a mate of my brother's.”

Armindo replaced his pistol in his belt. He snatched Dr. Murray’s flask and poured himself a glass. He took a long drink and stared at the Captain. “And you're also bloody lucky I hired you. Nobody else will...Dr. Murray.”

“What is it?”

“Ask the good Captain to tell you about the Lion of the Sea.”

At the mention of the ship’s name, I was certain I could see the Captain visibly cringe. He sank slowly into his chair as if he had suddenly become a very old man.

“I heard something about that ship. One of the best clippers ever built. She beat Sea Witch in a race, didn't she?”

“...Captain?! Dr. Murray asked you a question.”

“She almost did. A sudden squall took our stun’sails away at the last minute. We managed to rig up old awning and spare tarpaulin but in the end it was no use. We couldn’t catch the Witch.”

Armindo stood with one foot propped up on a low barrel, and the curled whip in one hand. “Tell Dr. Murray how your precious clipper ended up, Captain...The last voyage.”

Captain Elliott took a deep breath and let out a long sigh. He seemed to age even as he spoke. His bottle green eyes stared at no one and at nothing. “Like he said, the shipping industry had overbuilt. Too many ships, too little cargo. So I agreed to a coolie run to Havana. We picked up over a hundred coolies at Amoy and Namoa, two hundred here and another hundred in Macao...Anyway I had a bad feeling about it from the start. Damn owner was a pig-headed turkey-cock! Insisted we leave when we did. It was a Friday. Every seaman fears Friday's noon - 'Come when it will, it comes too soon'. But the run to St. Helena was uneventful. Not even that much sickness. Only six Chinamen died. I started to think we might be bung up and bilge-free, after all. We took on food and water then we set out for Havana.”

The Captain ran one wrinkled hand slowly and cautiously over his silvery white mutton chop whiskers as if searching for something he had lost in them; something very fragile. “On the third day, I heard a ballyhoo of blazes coming from the main deck so I rushed out and I saw some of the crew cutting the pigtails off the Chinese. They said the Chinamen were filthy and weren't washing properly so they were cutting the vermin-laden pigtails off and the Chinamen were screaming and crying in protest. I almost stopped them but I didn't...I wish to God I had.”

The silence lasted for several seconds. Captain Elliott seemed overcome with emotion and unable to continue. Armindo stared at him and spoke just above a whisper. “Captain?”

Captain Elliott turned to stare at Armindo and then looked away, again lost in the memories which haunted him.

“Anyway, after about an hour, I was in my cabin when the carpenter’s mate ran in to tell me the Chinamen had grabbed a rifle and a saber from my second mate and they were pelting us with anything they could rip up: belaying pins, iron rice buckets, firewood, our carpenter's hammers, anything. And they began setting fire to some of the wood. I gave the order to clear the decks and the crew began firing their rifles and revolvers and slashing out with their swords and forcing the Chinamen back. Everything got confused. Men screaming, guns being discharged, smoke billowing everywhere. Flintlocks, percussion caps, breech-loaders – whatever weapon we had seem to misfire. But we finally managed to get them below. Then we battened down the hatches and sealed all the deck openings. And we bolted iron bars to the coamings. They couldn't come up but most of the provisions and water casks were down below in the lower hold. In any case...”

Dr. Murray poured the Captain brandy in a glass and handed it to him. He took a long drink then let Dr. Murray take the glass from his hand. “In any case, I wasn't about to sail to Havana in that condition so I gave the order to return to St. Helena. When we got there, we summoned the local police. I thought if we got rid of the ringleaders, we'd be all right. So we opened the hatches...”

After a long moment, Armindo spoke softly but firmly. “Go on, Captain.”

“I thought...I thought the ventilation would be adequate. We had wind sails and scuttles! The ventilation trunks were...As God is my witness, I never intended...”

“What was down below, Captain?”

“...I lost all four hundred Chinamen...”

Armindo slammed his whip on the table causing all of us to jump. “What you lost was twenty-four thousand Spanish dollars!...And the Englishman who chartered the ship went bankrupt...So if I don't hire you, who else will? So you'll say 'Yes' and 'Amen' to everything I tell you. Is that clear, Captain?...Is that clear?!”

In the silence, we heard thumps against the exterior of the barracoon, against the door and walls. Armindo spun around with his hand on a pistol. “What in blazes?” He pointed to two of the crimps. “You. And you. See what that is.”

As the two crimps walked fearfully to the door and thrust it open, Armindo turned back to the Captain. “Is it clear?!”

The Captain gave him a vague nod. “Aye. That's clear.” And then his green eyes stared out from his weather-beaten face directly at Armindo. “But I've got a devilish bad feelin' about this business. We didn't let our anchors go to the windward of the law. Our joss is set.”

“You can prattle about joss all you like, Captain, just don't-“

The excited crimps had trouble closing the door. As they struggled to close it, bones blew into the barracoon. The first guard screamed. “Aiiiyaaah! The bones of the dead are hitting against the door! And the wall!”

The second crimp picked up a bone and held it close to a candle, then hurriedly threw it down. He screamed loudly about the bones of the dead seeking vengeance. There was already pure panic in his voice.

I could see the Chinese guards and crimps and coolies becoming agitated; some even moved toward the door. The one who had spoken first spoke again. “Aiiyaah! The bones of the dead are coming here!”

The excitement and fear spread through the barracoon like a fire raging out of control. Armindo turned to me. “What is it?”

“The bones of the dead! They're coming in!”

Coolies from the cockloft and from the darkness below began shouting in panic. “Help! The spirits are angry! The dead are rising!”

Armindo’s face clouded over with anger. “What the hell?”

“Bones. Dead men bones from outside!”

“Pipe down!” When his words had no effect, Armindo drew his pistols. “Goddamn ye! I said, pipe down!”

Captain Elliott slowly rose from his chair. “I smell hell.”

Bones of the Chinamen

Part 3 of 3

Armindo turned on him. “Shut your potato-trap!”

Armindo walked to one of the bones. He replaced one of his pistols in his belt and picked up the bone. He spoke to me while turning it slowly in his hand. “It's just a man's bone. It can't hurt anybody! Tell them.”

But I was also afraid. Afraid of the bones, afraid of Armindo’s wrath, and afraid that even he could not quiet their fear. I wanted to speak but no words came out.

Armindo turned to me and glared. The dark flesh of his left cheek bore red scratches from Tiang-si’s nails. He spat his words out at me. “Damn your eyes, tell them!”

“It is only a bone! You don't have to be afraid. Don't make the foreign-devil angry!”

Armindo walked toward the coolies and the crimps, holding the bone. They moved backward in fear. He pointed the bone at each in turn. “This...can't harm you.” He raised his pistol. “This can. The dead can't come back...Translate, damn you!

“The fire-stick can harm you; the bones cannot!”

Armindo’s words as well as his wrath had the desired effect of halting the spreading panic, but I knew from their frightened faces that it would be easy for the terror to take hold again. I saw him suddenly look up at the top of the stairs. When I followed his gaze, I saw Tiang-si staring down at the scene. Armindo placed his pistols and the bone on the table. “Enough of this. Time to scuttle the celestial ship.”

He slowly walked up the stairs to the cockloft while unbuttoning his clothes. “Li Tong! Untie the boy and put him with the others.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And my guts are so hungry they're cursing my teeth. Cook something up. I'll be even more hungry once I've finished up there.”

“...Yes, sir.”

As I untied the brother, he winced in pain. I walked him off into the darkness. The boy stared at me as we walked but spoke only when we were out of range of the others. “You must help my sister!”

“I cannot!”

“Li Tong, we have never met, but when I returned from Ningpo, my sister told me all about you. How she had loved you and would have married you; then found out you had joined with the pig sellers!”

“And now she hates me!”

“She loves you still! You need only quit this.”

“Why did Ah-fuk bring you here?! You were to be kept at the abandoned tea warehouse.”

“The tea warehouse was washed away by the storm during the night. So he and his men brought us here...But how do you know this?”

“It was...I paid Ah-fuk to kidnap you...and to send a message to Tiang Si. I thought if she believed you were kidnapped by the pig sellers she would have to come to me. But not here! You should never have been brought here; and she should never have come here!

He stared at me, then spat in my face. “You are worse than the outside barbarians!”

I watched him disappear into the darkness then walked slowly back toward the stove. I used a towel to wipe my face clean of his saliva. Even at that moment I knew this day would end only in disaster.

I put the kettle on for the water and left rice to steam. The pork and vegetables had already been prepared.

When I returned to the table I heard Dr. Murray speaking to me but I hardly made sense of it. “What is it, Li Tong? You look like a man sentenced to dance the Paddington Frisk...Well, my young friend, one thing I've learned in life: whenever the blue devils come, the best thing for them is a proper English breakfast or, if available, roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. But, failing those options, it's always best to fight them off with a swig from the foretopman's bottle.”

Dr. Murray poured himself a drink and was just about to take it when suddenly we heard the sounds of a female screaming. The sounds of slaps and the screams changed to the sounds of a woman groaning uncomfortably and rhythmically. Dr. Murray and Captain Elliott exchanged furtive glances then looked away in embarrassment. I stood motionless. Dr. Murray took his drink. Captain Elliot tapped the dead dottle from his pipe against the leg of the table then, almost as if the sound of his tapping had embarrassed him, he placed the pipe on the table and stared straight ahead, looking at no one.

In the silence we could hear the human-like roar of the wind as it hurled the bones against the exterior of the barracoon. They were thumping and rapping more frequently now. And with more intensity. But even they could not conceal the indescribable sounds from the cockloft. Sounds which, all these years later in every nightmare, are exactly as they were then.

As Tiang-si’s crying and moaning rose in volume, I moved, or found myself moving toward one of Armindo’s pistols. I placed my hand on one of them and looked up toward the cockloft. I heard the voices of Dr. Murray and Captain Elliott as the texture of one dream impinging on another. “Leave it be, Li Tong.”

“It's a bad business.”

“Aye, Captain, that it is. But his getting himself killed won't help her. Li Tong, leave it be!”

I wanted only for the horror to end. I quickly lifted the pistol and rushed forward. Dr. Murray and the Captain restrained me and we struggled. With all my strength, I tried to free myself from their grasp, but, in the end, the Captain managed to pry the pistol from my hand. Our struggle ended abruptly when Tiang-si gave one final loud cry of anguish.

No one moved. In the silence, there was a sudden pounding at the door. Again, Armindo’s men drew their weapons but this time they were obviously afraid. Some approached the front door with caution but others cowered away from the door completely.

The braver crimps threw open the door and a foreign devil rushed in, his head down to avoid the worst of the storm. The men struggled to close the door against the howling wind and pouring rain. I saw several more bones blow in.

The crimps saw the bones and ran off into the darkness. I rushed to close the door properly. The foreign devil assisted me. We finally managed to get it closed and barred.

I guessed the man to be in his late 20's or early 30's. He wore the clothes of an honest man – an old brown seaman’s frock which was nearly as frayed as his grey trousers and had been patched more than once. His handsome face was perfectly framed by his wide, low crowned hat. His eyes were a clear blue and his direct gaze seemed able to sum up the character of a man at a glance. He was clean-shaven and square-jawed and precise in his manner and words. The thought occurred to me that he could almost be mistaken for a missionary. He removed his hat and frock and with a nod of thanks handed them to me. I quickly hung them on a wall peg.

Armindo walked down the cockloft stairs while buttoning his clothes. “Who the deuce are you?”

Dr. Murray rose and gestured by way of introduction. “He's the emigration agent. Mr. Anderson. I told-“

“Ah! The totty-headed land shark who relanded my pork.”

As I listened to the emigration agent, I realized he was not the type of man to issue threats or speak gruffly. Rather, he spoke matter-of-factly with a somewhat prim, holier-than-thou manner. A manner which, to a man like Armindo, would be far more infuriating than threats.

“Yes. I relanded your pork. And I may be relanding a number of other items as well if I find they're not up to snuff. And before you receive any port clearance and certificate from me, I'll also ensure that you have ample medicines and water and provisions on board.”

“Is that all?”

“Not quite. You'll supply me with a complete passenger list and the contracts for every coolie. You will also not sail until you have a surgeon on board and an interpreter; an interpreter approved by me.”

“The hell, you say!”

“The hell I do say!”

“You can sooner whistle up a wind in the doldrums before I'll-“

“You will fulfill each and every article of the Chinese Passenger Act to the letter. Or else you won't be sailing.”

“Is that what you came here for? To fuss over the health of the Chinamen?”

“That. And to determine if these men truly wish to leave for Peru voluntarily.”

“The devil you will! That is done on board ship!”

“Not in this weather it isn't. It will be done inside the barracoon.”

“By whose authority?!”

“By my authority! The charter of conveyance of the subjects of China to the Chincha Islands will be carried out according to the provisions of the Chinese Passenger Act or it will not be carried out at all! And I suggest we get started.”

I honestly thought at that moment Armindo might strike him, but he took a deep breath and lowered his voice. “Your predecessor was a reasonable man, Mr. Anderson. There's no need for-“

“Let me make myself very clear, Mr. DaCruz. If I find that there has been any fraud or violence in your manner of collecting the emigrants, I will not merely void your contracts and let these men go, I will have you arrested.”

Armindo moved closer to the agent but the agent never flinched or gave ground. “You want to feel sorry for the Chinamen, is that it? Well, who the hell do you think brought the Chinamen here?! Chinamen, that's who. And who do you think brings the niggers to the ships in the Bay of Benin! Other niggers, that's who. We didn't even have to go into the interior to get 'em. Black tribes brought their captives and slaves down to our barracoons along the coast. The niggers couldn't sell each other to us fast enough. And John Chinaman is no different. They're fallin' all over themselves to sell their neighbors. They're kidnapping each other by force, they're feeding each other drugged cakes, spiked liquor, they're gambling each other out of their freedom, and they're trickin' each other into comin' here. I got two celestials came in here, each thinkin' 'e was bringin' the other. So I took them both and saved the money. The Chinamen are chasing the dollar more than we are! So don't try ridin' the high horse with me. We're providin' men an opportunity to sell their friends and neighbors for profit! And they're jumpin' at the chance!”

“Your type brings out the worst in men, that I grant you. But there are placards all over southern China offering rewards for those involved in the slave trade. Some Chinese crimps have already been executed. And without you and your men, the Chinese kidnappers would have no protection.”

Captain Elliott pinched some tobacco from a pouch and refilled his pipe, then again circled the bowl with his match until the flame dipped. He spoke as if in awe of the scene he was describing. “Aye! I've seen what the mandarins do to kidnappers. They nail them up facing the sun. Then they cut their eyelids off so they can't blink. That way they go painfully blind, then die of thirst.”

“Damn your eyes! I warned you to clap a stopper on your tongue!”

Dr. Murray’s voice was slurred. I remember thinking he was too intoxicated to have heard the murderous anger in Armindo’s warning. “Aye. And any woman involved has her breasts cut off as well! When I was outside Ningpo, I saw that pretty sight.”

The agent looked at Dr. Murray with undisguised disdain. “Is this man the physician who has examined these men?”

Dr. Murray seemed to take the question as a compliment. “The very same, sir.” As he placed his glass to his mouth, Armindo violently thrust it out of his hand. It sailed across the room and smashed.

“Blast you! You're already three sheets to the wind and the fourth's shaking!”

Dr. Murray held tightly to his walking cane. “You lubberly fellow, if I were a younger man I'd give you a clout on your jolly knob!”

The agent had obviously seen and heard enough. “Assemble your coolies, Mr. DaCruz.”

Armindo hesitated then gestured to the crimps to bring out the coolies. As they brought some of them forward, I could see the shadows of others in the background, some silent and sullen, some silent and defeated. But I could also sense that their terror and fear of the bones was growing. One of the coolies in the front row was Tiang-si’s brother. In the silence, I heard again the sounds of bones hitting against the exterior of the barracoon. Like dead men knocking.

Bones of the China: Part 3 of 4